In 1919, Lenin wrote, “Productivity of labour is the most important thing for the victory of the new social system…Capitalism can and will be utterly vanquished by socialism creating a new and much higher productivity of labor.”

For a while, it seemed that Lenin’s prophecy was coming true. The USSR was doing better than any other developing country in catching up with the West, at least for a while. Soviet development looked extremely impressive until the 1970s. In fact, from the 1920s until the 1960s, the USSR and Japan were the only two major developing countries that successfully, if only partially, bridged the gap with the West (see Figure 1).

For centuries, Russia consistently fell behind the West. Neither the reforms of Peter the Great in the early 18th century, nor the elimination of serfdom in 1861, nor Witte’s and Stolypin’s reforms in the early 20th century could change that trend. Only between 1920-1960 did Russia (USSR) start to catch up with the West (see Figure 1).

Despite the popular belief that Soviet economic development was a failure, from 1928-1970 the USSR had the second fastest growing economy in the world after Japan (Allen, 2003, fig. 1.1, p.7). Many developing countries were trying to copy the Soviet model in the 1950s-60s, even though Soviet assistance at that time was minimal and far below Western levels of assistance. The Soviet model at the time was probably no less attractive for the developing world than the Chinese economic model today.

Francis Spufford’s 2010 novel Red Plenty nicely captures the atmosphere when there was the sincere belief that the gap between the USSR and the West was narrowing and would soon disappear not only because socialism was a more advanced “social” system but it also provided a more competitive economy. Even in the 1970s, when the catch-up was coming to an end, there was hope that Moscow would glitter brighter than Manhattan and Ladas would be better engineered than Porsches.

During the famous “kitchen debate” of 1959, Nikita Khruschev famously refused to admit that capitalism led to better innovations. When opening an American exhibition in Moscow, Richard Nixon, then serving as vice president, stated, “You are ahead in space; we are ahead in color TV. Let’s compete for the benefit of consumers in both countries.” But Khruschev raised his hand in objection, stating that the USSR had surpassed the U.S. in rockets and would also surpass them in TV. Many around the world believed Khruschev, as was customary for that time.

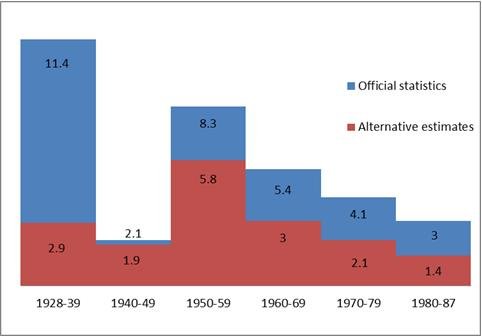

In the second half of the 20th century, the Soviet Union experienced a dramatic shift in economic growth patterns. The high post-war growth rates of the 1950s gave way to the slowdown of 1960-1980 and led to the unprecedented depression of the 1990s associated with the transition from a centralized to a market economy. Productivity growth rates gradually fell from an exceptionally high annual rate of 6 percent in the 1950s to 1 percent in the 1980s (see Figure 2).

The Soviet Union’s transformational recession started in 1989 and continued for about a decade. In Russia, output continuously fell until 1998 with the exception of 1997 when GDP increased by a barely noticeable 0.8 percent. If viewed as an inevitable and logical result of the Soviet economic model, this recession substantially decimates Soviet economic growth trends.

Anecdote: “Soviet Ministers Visit Honduras”

In 1964, Honduran Minister of Communications Rodriguez received Minister Ivanov, his Soviet counterpart, in Tegucigalpa. After formal talks, Rodriguez invited Ivanov to his hacienda. He showed Ivanov his seven bedroom mansion, swimming pool, garages, hectares of orchards, and domestic servants. He took him for a fishing trip on his personal yacht and offered him a luxurious dinner with exotic foods. He gave him a ride in his limousine and told of how his children were studying at Ivy League universities in the United States. Ivanov, was not discouraged and not impressed. He knew that the people of Honduras were poor and many were starving. In the Soviet Union, he knew that while living standards were lower than in the West, there was no starvation. He knew that life expectancy in the Soviet Union was twenty years higher than in Honduras. Soviet scientists were receiving Nobel prizes, Yuri Gagarin was the first man in space, the Soviet ballet was the best in the world, and Soviet nuclear submarines could roam the far seas. He was proud that his state was building the most advanced and socially equal civilization in human history.

Twenty years later in 1984, Minister Petrov, Ivanov’s successor, visited Honduras to talk with his counterpart Minister Gonzales, the successor of Rodriguez. He was unpleasantly surprised and even a little irritated by what he discovered. Over the past two decades, Honduran life had unexpectedly risen from 50 to 65, whereas Soviet life expectancy had signs of decline. He realized that even though the USSR was more technologically advanced and economically more developed than Honduras, he would never have the same living standards as Gonzales. Why? Didn’t he deserve what Gonzalez had more than Gonzalez? After all, Russian submarines were roaming the oceans and the USSR was leading the world in the arts, science, and even in space exploration. Why should we endure increasing deprivation for the sake of great and noble goals? It dawned on him that even though the Soviet Union was “growing faster than the West,” so were its many struggles, causing him to think, “Why bother with socialism? If the USSR had capitalism, I would be far better off than Gonzales!”

Though this story is fiction, it captures the change in mood of the Soviet elite when the Soviet system had lost its dynamism. The Soviet Union’s political, technical, and intellectual elite were loyal to the USSR despite its lower welfare standards compared to Western countries, but they were inspired by economic indicators, chiefly the constantly reducing gap with the West when it came to aspects such as per capita income or life expectancy. These elites believed that socialism was ideologically superior and that it could beat out capitalism once it was “fully developed,” but the flaws in the model meant that it could never reach its idealized end-stage. When the USSR stopped growing faster than the West in the 1970s-80s, this belief system was shaken.

Socialism: The Alter Ego of Capitalism

The breakdown of global socialism was ambiguous and even treacherous. In a sense, the collapse of socialism played a bad joke on capitalism. Socialism was the alter ego of capitalism in that it created checks and balances on the capitalist model; it forced a limit to capitalist profiteering and the introduction of social programs within the capitalist doctrine. Unconstrained capitalism, without the moderating impact of socialism, is likely to repeat the mistakes that it committed a century ago that led to the emergence of socialism in the first place. Left without an alter ego, a bullish capitalist system may drive inequality to the point of unbearable social tension leading to another episode of self-destruction for capitalism.

———–

Also see in this series: Vladimir Popov, A Brief Look at Russian Economic Nostalgia and the "Equal Opportunity" vs. "Income Equality" Debate, Nov. 19.

———–

Figure 1 (in three charts). PPP GDP per capita in the USSR and Russia, % of Western European and US level

Source: Maddison, 2010.

Figure 2. Annual average productivity growth rates in Soviet economy, %

Source: Easterly, Fisher, 1995.

References

Allen, Robert C. (2003). Farm to Factory: A Reinterpretation of the Soviet Industrial Revolution Princeton University Press, 2009.

Easterly, W., Fisher, S. 1995. The Soviet Economic Decline. – The World Bank Economic Review, Vol. 9, No.3, pp. 341-71.

Khruschev, N., Nixon, R. (1959). The Kitchen Debate, 1959, U.S. Embassy, Moscow, Soviet Union.

Lenin, V. (1919). “A Great Beginning”, Collected Works, Volume 29, pp. 408-34,

Progress Publishers. Online version 1996-99.

Maddison, A. (2010). Statistics on World Population, GDP and Per Capita GDP, 1-2008 AD (http://www.ggdc.net/MADDISON/oriindex.htm)

Spufford, Francis (2010). Red Plenty, Faber and Faber Ltd., London, 2010.