(PONARS Policy Memo) Russia’s swift achievement of its political objectives in Crimea while firing hardly a shot generated much debate about the use and effectiveness of “hybrid warfare.” Although the term lacks a clear definition, it refers to Moscow’s use of a broad range of subversive instruments, many nonmilitary, to further the Kremlin’s domestic and international interests. While Russia’s use of hybrid strategies has grown markedly in recent years, it experimented with them in its conflict with Georgia in 2008. One of these actions is the ongoing, unilateral “borderization” of territory between Georgia and its breakaway regions Abkhazia and South Ossetia. The creation of these dividing lines on the ground violates Georgia’s territorial integrity and sovereignty, deepens the estrangement of Abkhazians and South Ossetians from Georgia, and undermines the wider European security order. Russia’s violations of Georgia should be viewed by the international community as illegal, unacceptable, and met with stiff counter policies.

What is Borderization?

In August 2008, Georgia and Russia endorsed the Six-Point Ceasefire Agreement that ended the conflict. Shortly after this agreement was signed, Russia began to cordon off the occupied territories in a process called borderization. This has been occurring, in the most noteworthy case, along or near the Administrative Boundary Line (ABL) demarcating the Georgian boundary with the South Ossetia/Tskhinvali region. (Most of Abkhazia is demarcated by the natural boundary of the Inguri river.) This borderization is an ongoing problem for Georgia, which sees it as the “creeping annexation” of territory by Russia. Moscow has been doing it gradually to avoid provoking a backlash.

As a July 2017 article in Foreign Policy remarked:

“Just before President Donald Trump and President Vladimir Putin’s tête-à-tête at the G-20 on July 7, Russia quietly annexed ‘about 10 hectares’ of Georgian territory on behalf of the Republic of South Ossetia, a polity recognized by just four countries (including Russia). The move went largely unnoticed except, of course, in Georgia proper, where President Giorgi Margvelashvili decried ‘creeping occupation.’ That generalized silence is what the Kremlin was counting on.”

A fairly new phenomenon, borderization is a euphemism for what are in fact continuous acts of war: the unilateral advance by one country’s military forces onto the territory of another.[1] For Georgia, it specifically refers to the installation of border markers, fencing, and barbed wire along the ABLs that separate Abkhazia and South Ossetia from the rest of Georgia. In some cases, it involves the seizure of additional land. In all cases, it splits communities and causes unnecessary tensions.

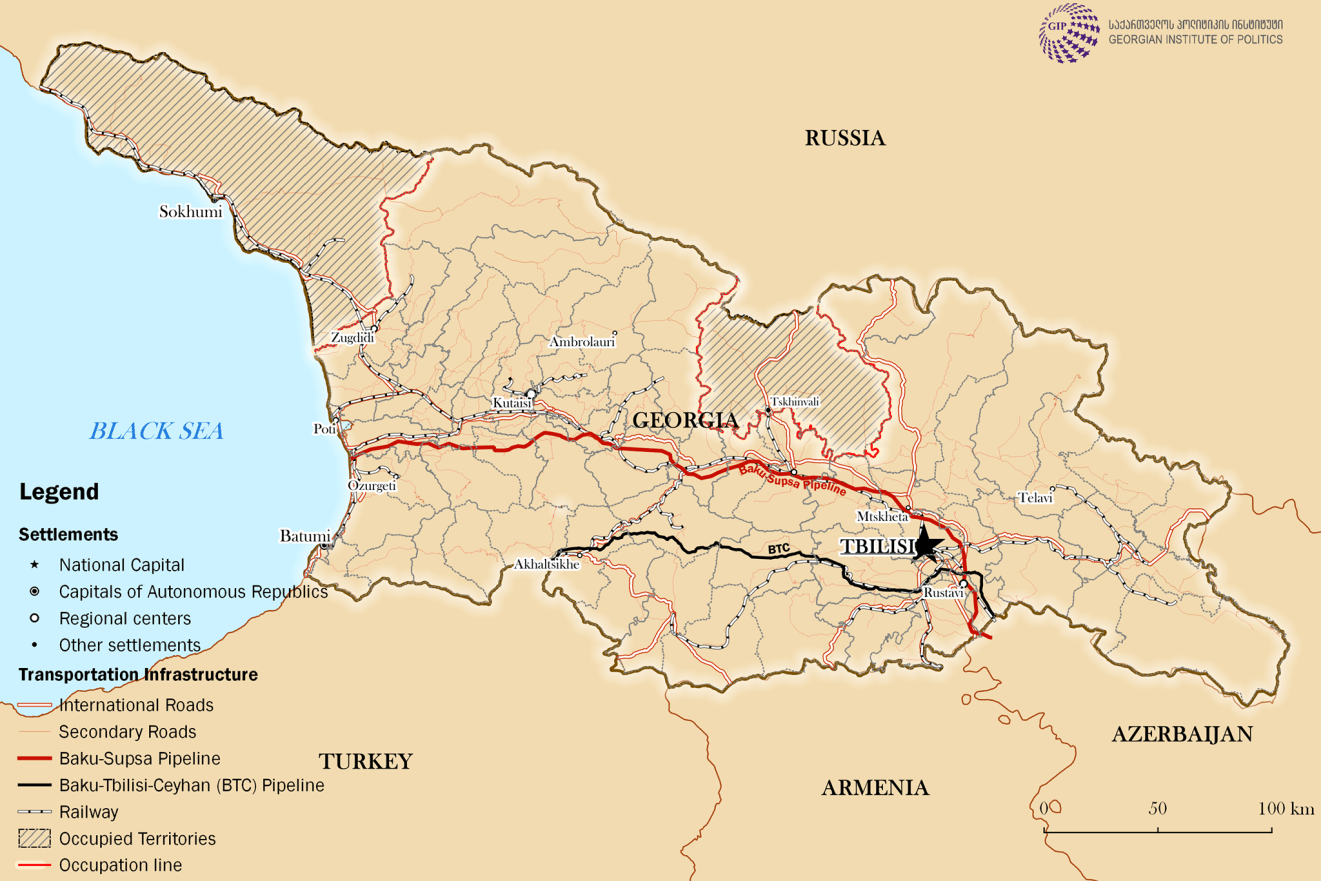

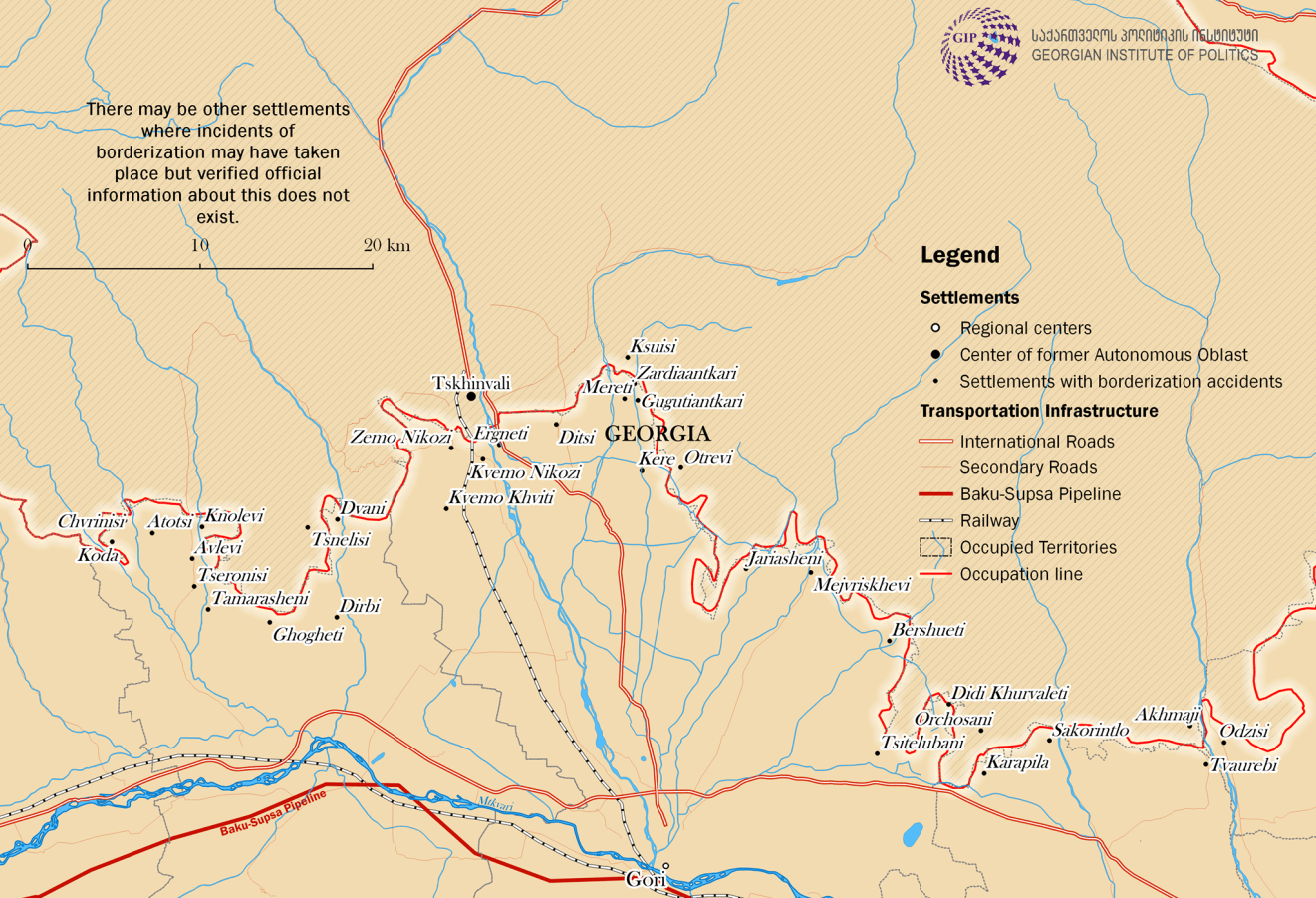

Russia has undertaken the borderization of Georgia’s occupied territories in waves. In April 2009, the Russian government and the de facto authorities in Sukhumi and Tskhinvali signed respective agreements granting the Russian FSB border units jurisdiction over the ABLs. In a series of borderizations beginning in the spring of 2013, Russian soldiers and ethnic Ossetian militia installed barbed wires fences to demarcate South Ossetia. This moved the ABL deeper into Georgian territory, seizing pieces of territory hitherto under Tbilisi’s control. The process picked up in intensity starting in the summer 2015 when Russian soldiers and Ossetian militia installed border markers in the village of Tsitelubani (near Tskhinvali). This incident resulted in a portion of the BP-operated Baku-Supsa oil pipeline being included in the zone of Russian occupation (see the two maps in Figure 1).

Figure 1. Borders, Settlements, and Transportation Infrastructure

Source: Georgian Institute of Politics

Borderization and Russia’s Strategic Objectives

With its decision to recognize Abkhazia’s and South Ossetia’s self-proclaimed independence, Moscow disqualified itself as a potential mediator in Georgian conflict resolution and officially became party to the conflict. By building physical barriers, Russia adds unchallenged permanence to the theft of Tbilisi’s territory. Moving the ABLs deeper into Georgian territory also serves a tactical purpose. From its new forward positions, Russian armed forces can more easily disrupt key pieces of nearby infrastructure such as the Baku-Supsa pipeline and the important Georgian East-West Highway. It can also more easily menace major population centers, including Tbilisi. Borderization achieves five Russian strategic objectives:

• Creates “new facts” on the ground that serve to weaken Georgia’s sovereignty.

• Gives Russia the ability to easily disrupt hydrocarbon and transportation veins.

• Unleashes forms of psychological warfare against Georgian society (leading the Georgian public to lose confidence in their government).

• Impedes NATO integration by ensuring that Georgia has a permanent conflict on its territory.

• Demonstrates to the Georgian public that NATO and EU cannot solve their problems.

By limiting person-to-person contacts and preventing residents of the occupied territories from accessing public services, Russia’s borderization policy deepens Tbilisi’s estrangement from its ethnic minority populations.[2] While the Georgian government has promised to share all of the benefits of its EU integration path with residents of the occupied territories, their further isolation disrupts the process toward reconciliation and reintegration.

Implications for Georgia’s National Security

Since 2014, Moscow has taken new steps in its creeping annexation of Georgian land. It has been establishing military bases in the borderlands and does not allow the EU Monitoring Mission (EUMM) to visit certain areas. In a further grave violation of the August 2008 Ceasefire Agreement, Moscow signed the so-called “treaty on alliance and strategic partnership” with Abkhazia in 2014 and the so-called “treaty on alliance and integration” with South Ossetia in 2015. These agreements seek to advance the integration of these areas militarily and economically into Russia.

The treaties cover the following main Russian priorities by:

• Establishing a coordinated foreign policy and common defense and security space (Combined Group of Forces).

• Creating a Joint Coordinating Centre for law enforcement agencies (under the FSB system).

• Implementing a common social, economic, and humanitarian space (simplified procedures for obtaining Russian citizenship; bringing pensions and salaries to levels equivalent in Russia’s southern regions).

• Enhancing the breakaway regions’ participation in Russian-led regional economic integration initiatives, including a commitment to harmonize their customs regimes with the Eurasian Economic Union.

The Abkhaz militia began to integrate into the Russian armed forces in 2015. By 2017, 4,500 local soldiers directly under Russian military command were based in Abkhazia. In March 2017, Russia and the de facto Tskhinvali authorities signed an agreement to formally merge the region’s militia into the Russian armed forces. Such steps by Russia and the de facto authorities in the breakaway regions further erode Georgia’s sovereignty and pose vital challenges to its national security. Even though Georgian authorities claim that there are no direct and immediate threats from these militarization processes, having regular, Russian-led, military trainings just a couple hundred meters from Georgian citizens leading “normal lives” (and the strategically important East-West highway) should definitely be seen as threatening and increases Georgia’s insecurity.

Human and Political Costs of Borderization

According to information provided by the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Georgia, after the war in 2008, the Georgian state lost control of 125 settlements: 103 in South Ossetia/Tskhinvali and 22 in Abkhazia. Borderization has grave human costs for the local communities affected. Displaced Georgians from previous years became twice affected. Villages became separated by barbed wire and local residents lost access to their homes and farmland. Some local residents had to flee their longtime homes, thus launching another wave of displaced people. It has created hardship for residents seeking to visit relatives or get medical care, attend schools and colleges, and pursue economic opportunities in Georgia. The negative impacts of borderization are felt by local communities regardless of ethnicity. It violates the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights in a number of areas, including freedom of movement and freedom from arbitrary arrest and detention. Since April 2016, three official crossing points between Abkhazia and the rest of Georgia have been closed off, increasing the territories’ isolation from the rest of the country.

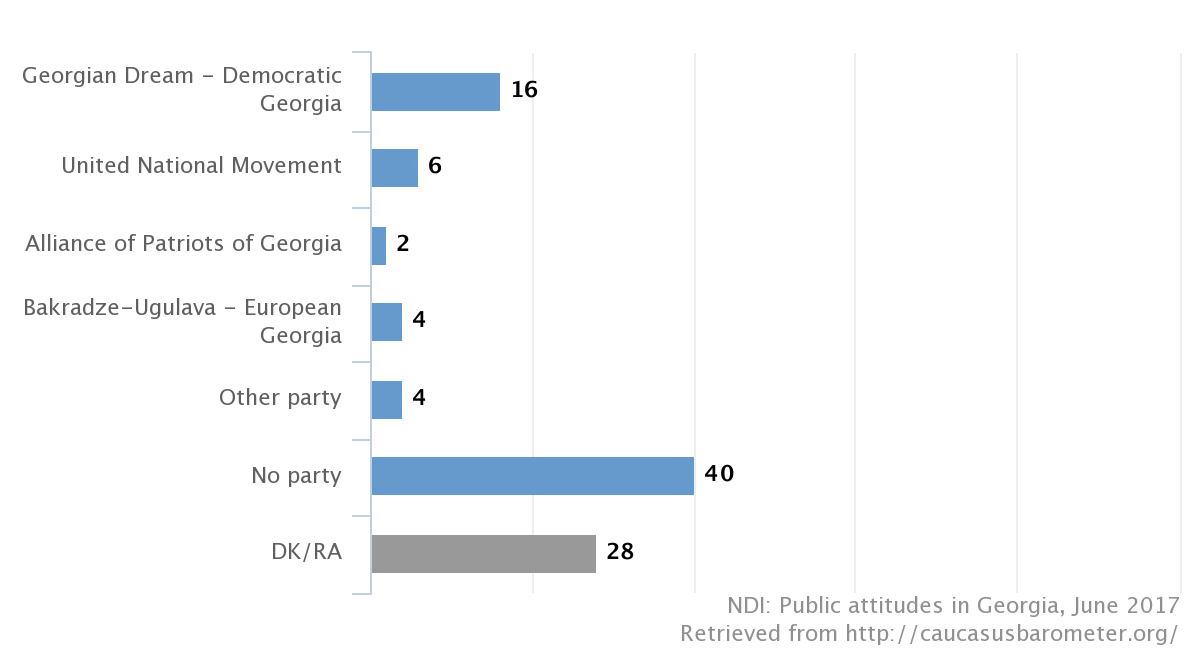

Borderization has also had poisonous effects on domestic political discourse. While the Georgian government condemns it as a deliberate provocation aimed at destabilization, it lacks the tools to deter Russia’s use of the tactic. The Georgian public has been responding with outrage each time a new border installation is erected. This is mostly directed against Russia but it is sometimes pointed at the Georgian government, which is viewed as weak and ineffectual on matters involving territorial integrity. Indeed, the government has been unable to respond assertively to Russia’s borderization maneuvers. According to a June 2017 poll by NDI and the Caucasus Research Resource Center, only 16 percent of Georgians said they trusted the current ruling party to effectively manage the issue. By contrast, 40 percent reported trusting no party and 28 percent could not answer the question (see Figure 2). Injecting anxiety into Georgian society saps legitimacy from the current regime and disrupts the normal functioning of government, playing into Russia’s hands.

Figure 2: Which Political Party Do You Most Trust to Manage “Restoring Territorial Integrity?” (%)

Source: Online Data Analysis (2017), Caucasus Research Resource Center (CRRC)

Borderization also strengthens two Kremlin narratives being disseminated in Georgia: first, that Georgia’s Western allies (especially NATO) are unwilling or unable to help it restore its territorial integrity (making Euro-Atlantic integration pointless); and second, that Russia holds all the cards and therefore the Georgian government has no choice but to make concessions. As Russia deepens its occupation and NATO and EU member states fail to address its actions, Georgian public confidence in both institutions is eroded. The main international force on the ground, the EUMM, which was deployed to Georgia in September 2008 to, among other roles, prevent further instances of borderization, is not seen as credible or viable as a Georgian security partner.

What Can the International Community Do?

Russia’s borderization schemes will continue as long as costs are not imposed on Moscow. The Georgian government is unable to impose pressure points unilaterally, therefore the response must be international. The West should treat Russia’s violations of Georgia’s sovereignty and territorial integrity as it treats Russia’s annexation of Crimea and incursion into Donbas: as illegal and unacceptable. To change Russia’s strategic calculus, an assertive Western response is needed involving a coordinated anti-annexation policy (with possibly targeted sanctions) and placing troops and more international observers at the ABLs. The international community should draw attention to Russia’s failure to uphold the 2008 ceasefire agreement and increase calls to allow EUMM officials access to Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Even if only a partial measure, a full-fledged, functioning EUMM could help facilitate mutual trust along the ABLs. Russia should be leaned on to demilitarize the ABLs, allowing for buffer zones that would reduce tensions and bring immediate day-to-day benefits to local residents on both sides. All parties should be encouraged to continue constructive negotiations, including through the UN Geneva format—although by now, a significant portion of Georgians have lost confidence that talks will yield tangible results. Money is also a lever, and Moscow’s is not limitless: Georgia’s Western allies could provide financial support for improved public services for residents in the breakaway regions, as well as direct financial support for internally displaced peoples. Any and all of these steps would help mitigate the isolation felt by residents in the occupied areas.

Conclusion

The hybrid warfare and borderization strategies used by Russia in Georgia pose a clear challenge to Western interests and the wider European security order. By keeping the conflict unresolved, Moscow positions itself as the dominant actor not only in Georgia’s neighborhood but also in the wider Black Sea region. Russia has troops positioned in Georgia, an openly aspiring NATO and EU member. As The New York Times wrote, when Russia recognized South Ossetia’s claims to statehood after the 2008 war:

“…the territory joined Abkhazia in western Georgia, the Moldovan enclave of Transnistria and eastern Ukraine as a “frozen zone,” an area of Russian control within neighboring states, useful for things like preventing a NATO foothold or destabilizing the host country at opportune moments.”

Erecting barriers not only violates the human rights and freedom of movement of local residents on both sides, but leads to frustrations across Georgia that are often directed back at NATO and the EU for not having helped the country solve its most pressing national problem. The entire situation is exacerbated by the fact that quality regional data collection and interagency cooperation are lacking. The known problem is that Tbilisi’s toolkit for responding to Moscow’s tactics is limited. While this delicate situation keeps the Georgian government under pressure, the risk of unintended incidents grows in a region where security and peace often hang by a thread.

Kornely Kakachia is Professor of Political Science at Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University and Director of the Tbilisi Georgian Institute of Politics. This policy memo is based on a more detailed study co-authored by Kornely Kakachia, Levan Kakhishvili, Joseph Larsen, and Mariam Grigalashvili, “Mitigating Russia’s Borderization Of Georgia: A Strategy To Contain And Engage,” Georgian Institute of Politics, December, 2017.

[PDF]

[1] See: “How Should Georgia Respond to Russia’s Borderization? Expert Comment,” Georgian Institute of Politics, August 2017.

[2] See: “On the Impact of the Closure of Crossing Points on the Rights of the Population Living Along Abkhazia’s Administrative Boundary Line,” Special Report, Public Defender of Georgia, November 2017.