(PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo) Georgian parliamentary elections are scheduled for October 31, 2020. The convention in Tbilisi is that no political party has stayed in power beyond two consecutive terms, and Georgian Dream’s second term concludes this fall. Even though it is only a tradition, it opens the way for political formations to change. Instead of one ruling party or electoral bloc, the future government may be a coalition of forces. Although the current government, informally headed by billionaire Bidzina Ivanishvili, received some support recently for its anti-coronavirus measures, the population clearly distrusts the current political elite and is disappointed in political processes. A public opinion poll in late February 2020 by the Caucasus Research Resource Center showed that 80 percent of Georgians considered it necessary for a “new political force” to take over.

The people have lost confidence in both the current government and the political opposition. With many voters searching for new policies, what are the preconditions and chances for the creation of a coalition government as a result of the elections? Georgian Dream and its nemesis United National Movement remain at the top of the standings out of many political parties, but the two-term tradition, the generally fallen rankings of the two leading parties, and the high levels of undecided voters indicate that new alliances and ministerial faces are probable.

Undecided Voters Waiting for Godot

Since the adoption of the 1995 constitution, only one party has received the majority of mandates in parliament and, accordingly, a monopoly on government formation. In 1995-2003, the Union of Citizens of Georgia headed by Eduard Shevardnadze had a monopoly on power. In 2003-2012 it was United National Movement headed by Mikheil Saakashvili. Since 2012, Georgian Dream has been in control. Today, multiple surveys indicate that the population is tired of such political monopolies, but is still hesitant about drawing in other actors and parties.

Georgia has a high number of undecided voters. According to a public opinion poll this summer by Edison Research, over 20 percent of voters have yet to decide who to vote for in the upcoming parliamentary election. A survey project by the International Republican Institute (IRI) also this summer found the number to be as high as 50 percent. Capturing the choices of neutral voters is the main objective of the traditional parties and, at the same time, a strong incentive for the creation of new political structures.

Recently, many new parties have been created that claim to offer an alternative or a “third party” choice. For example, the Lelo party was created by famous Georgian businessman and multi-millionaire Mamuka Khazaradze, along with several other new parties that have also been vying for the status of fresh and new. They position themselves in opposition to both the current authorities and also to the official opposition party, United National Movement. But when it comes to being “new forces,” Lelo, for example, has among its leaders a former parliamentary chairman, former parliamentary members from Georgian Dream, advisers that served fourth president Giorgi Margvelashvili, former high-ranking officials from the administration of third president Saakashvili, and a privileged businessman (and former personal pilot) of second president Shevardnadze. Such new political bodies look like outdated products in new packaging.

As polls show, despite efforts to form a third force in the country before the October elections, the main rival parties will be Georgian Dream and United National Movement. Since 2012, Georgian Dream has been trying hard to drive its rival out of the field, which has included behind-the-scenes efforts to create new, alternative forces that could play roles as “constructive” opposition. For example, over the past year, many members of parliament have split from Georgian Dream. Some have created their own parties. While they may never personally criticize Ivanishvili, they often criticize United National Movement. At a pre-election public event this month, leaders from the current ruling party and the country’s defense minister clamored that the removal of United National Movement from politics was “an overall national task.“

Only these two parties have a solid and stable electorate of their own, although they may not have enough for either of them to win a complete victory in the elections. If the elections prove to be free and fair, neither of these two parties will be unilaterally able to form a parliamentary majority. According to a public opinion poll by IRI this month asking which party the person would vote for, 16 percent said for United National Movement and 33 percent said for Georgian Dream. On the same question, Edison Research found the numbers to be 16 percent for United National Movement and 39 percent for Georgian Dream.

Barriers Lowered and Barriers Raised

According to the constitutional changes approved at the end of June 2020, which were based on the demands of the opposition and under pressure from Western partners, Georgian Dream’s chances of forming a parliamentary majority have been sharply reduced. Previously, the ruling party took a parliamentary majority with the help of majority members of parliament. In the upcoming election, 120 deputies will be elected from party lists (rather than 77) and only 30 deputies from single-seat majoritarian electoral districts (rather than 73). The reduction in the number of majoritarian electoral districts will weaken the position of Georgian Dream because, traditionally, in almost all majoritarian districts, government candidates always win (thanks to bribery, informal local ties, etc.).

Moreover, the authorities, on their own initiative, introduced another amendment that lowered the electoral threshold from 5 to 1 percent: “mandates… shall be distributed to the political parties that receive at least 1 percent of the valid votes of the voters, and to the electoral blocs of those political parties.” In conditions of low support and with less majoritarian electoral districts, a 1 percent barrier would encourage Georgian Dream to promote other, smaller parties during the elections. Its strategists hope this manipulation will succeed in forming a parliamentary majority and a pro-government coalition government. The introduction of the 1 percent barrier indicates that the ruling party is no longer confident in its own success in the October elections. Thus, one of the likely scenarios it considers after the elections is the creation of a coalition government together with loyal and satellite small parties.

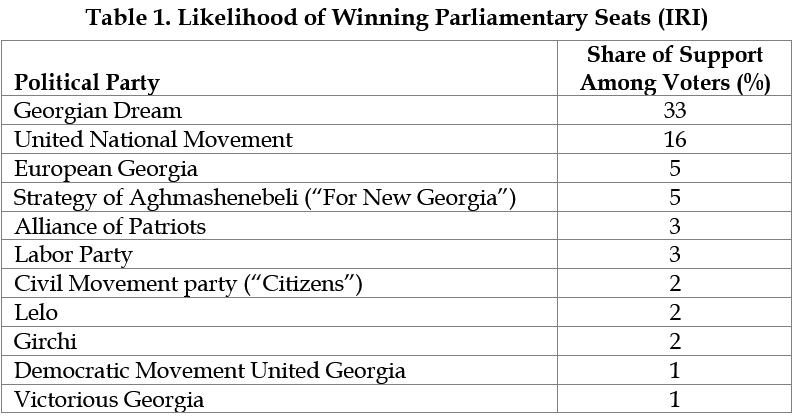

During the 2016 parliamentary elections, only 3 parties were able to pass the 5 percent threshold: Georgian Dream with 44 mandates (48 percent), United National Movement with 27 mandates (27 percent), and Alliance of Patriots with 6 mandates (5.01 percent). Under the new rules and 1 percent barrier, there is a high probability that at least 11 political parties can receive parliamentary mandates. According to the IRI survey project, the following parties are likely to win parliamentary seats, with polls showing they have the following shares of support among voters (see Table 1).

It would be logical for the majority of the small parties to choose to join the opposition coalition. However, the ambitions of some of their leaders may play into the hands of the authorities. At the same time, among these parties, there may be those who unofficially receive financial support from government-supported businessmen. For example, although unconfirmed, there are suspicions that Strategy of Aghmashenebeli receives financial support from businessman Ivane Chkhartishvili. He is a former official and deputy prime minister of Georgia during the Shevardnadze era and today he is considered Ivanishvili’s main business partner. He is involved in political life and one reason for the suspicions is that he is the closest relative of party leader Giorgi Vashadze.

Orientations and Personalities

Most Georgian political parties are pro-Western and support the country’s integration with NATO and the EU. The exceptions are Alliance of Patriots and Democratic Movement United Georgia, which are both “pro-Russia” parties. The first party is led by David Tarkhan-Mouravi, who claims to be the heir of several branches of the royal dynasty of Georgia at once. He was also a former official under Shevardnadze. The party has another leader, Irma Inashvili, who is the current vice-speaker of parliament. She is a former journalist, adores Russia, and hates the United States/NATO. The other party is led by Nino Burjanadze, who was the acting president of Georgia during the 2003 Rose Revolution. Alliance of Patriots receives some support from the ruling party, but, all in all, neither party is popular with the electorate. In the 2016 parliamentary elections, Alliance of Patriots managed to overcome the 5 percent barrier thanks to some selective manipulations and the informal financial and political support from the partly pro-Russian[1] Georgian Dream.

As for political ideology, Georgian Dream positions itself as social-democratic while United National Movement claims it is centrist/center-right. However, in the past, as the ruling party, it was more right-flank. To touch briefly on several others, Alliance of Patriots leans ultra-nationalist, European Georgia is liberal, and Girchi is ultra-liberal and advocates for the abolition of state institutions. Lelo should have a right-wing orientation, but among its leaders are left-wing activists. The leader of Сitizen/Civil Movement rejects any ideology and calls only for “service to the people.“ All parties are characterized by populism. The main point in the current analysis is that the opposition parties collectively could get more votes than the current ruling party, giving a chance for the formation of a coalition government for the first time in the country’s history. Will they unite against Georgian Dream, or will some create a coalition with it? This will largely depend on the personal ambitions of the party leaders.

A rating of a party can differ sharply from public opinions of party leaders. This provides some leaders the incentive to press for the position of prime minister, even if their parties still only receive a bare minimum of votes. Some party leaders already claim that they will be the future prime minister, whether the public favors them or not. For example, Vashadze, head of Strategy of Aghmashenebeli and former Deputy Minister of Justice under Saakashvili, has presented himself as the most suitable candidate. In IRI’s public opinion survey asking which politicians and public figures were favorable or unfavorable, he placed 7th out of 20. Vashadze hopes to take this position as part of a future coalition government and has called on the opposition parties to support his candidacy. Meanwhile, Lelo and its leader, the wealthy and well-known Khazaradze, is also angling for the prime ministerial position. He placed only 16th out of 20 in IRI’s “favorability” question. European Georgia, which has several deputy mandates in the current parliament, is also confidently saying that their candidate, David Bakradze, would be the best prime minister. He is in 3rd place in the survey indicating the public sees him favorably. Bakradze led the Georgian parliament during the Georgian-Russian war in 2008.

United National Movement is apparently considering promoting former president Saakashvili as prime minister, even though he does not have Georgian citizenship and lives in Ukraine. Saakashvili is still the unofficial leader of United National Movement and says he plans to leave Ukraine and return to Georgia, presumably with becoming prime minister in mind. As for Georgian Dream, current Prime Minister Giorgi Gakharia ranks in first place (IRI)—several points ahead of the country’s informal leader, Ivanishvili, who will nonetheless decide his party’s candidate and may select a complete “unknown” if he so desires.

Conclusion

Competing designs on the position of prime minister and the personal ambitions of some of the political leaders in the opposition could prevent opposition forces from forming a coalition government. Some evident disunity can be seen by how no party supports Vashadze’s candidacy for prime minister even though the man himself is still conducting an active public relations campaign with slogans such as “Vashadze—Prime Minister!” All the while, both his personal and party popularity ratings are low (still, his party should be able to gain more than 1 percent and receive several deputy mandates). In another example of rifts, European Georgia is categorically against Saakashvili becoming prime minister.

If Georgia manages to hold fair elections in October and, in the aggregate, opposition parties receive more votes than Georgian Dream (all surveys are indicating this), the creation of a coalition government will be a challenging test for the political class. One uncertainty is that we cannot currently predict what the 20-50 percent of the neutral/undecided voters will do. What if the elections are not free and fair? Falsification and bribes are possible. If Georgian Dream retains power through manipulation, Georgians, like Belarusians, have a rich experience of activating street pressures and protests.

Dr. Beka Chedia is a political scientist from Tbilisi, Georgia. He was recently a professor and country expert for the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) research institute at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden.

[PDF]

[1] See: Beka Chedia, “The battle of the USSR in Georgia rages on,” New Eastern Europe, January-March 2020, p. 53.

Homepage image credit.