(PONARS Policy Memo) The U.S. government spent $1.9 billion on security assistance to Central Asia between 2001 and 2016. The aid was designed to increase the professionalism of Central Asian ground troops and train and equip security personnel in counterterrorism and counter-narcotics operations. All Central Asian states saw some improvements to their internal security forces as a result. However, two major incremental trends were not addressed through these efforts: opium trafficking from Afghanistan and “authoritarian-ization” across the region. Washington’s support to Central Asia—even with the Trump administration’s proposal of halving financial assistance to the region—will be detrimental to U.S. national interests if it is not leveraged by measurable progress in host governments’ program-related achievements. Building state capacity without commensurate accountability, transparency, and anti-corruption expectations can easily make it possible for the region’s authoritarian governments to strengthen themselves without meaningfully combating the transnational security threats.

Taking Stock of U.S. Security Aid to Central Asia

Central Asia acquired geo-strategic importance for Washington in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks. The United States placed high priority on addressing regional insurgency spillovers and the logistical demands of supporting a large-scale US-led military campaign in Afghanistan. In exchange for access to Central Asian airspace, transportation infrastructure, and military facilities, the U.S. government provided the five republics with over $3.2 billion in security and economic assistance between 2001 and 2015.

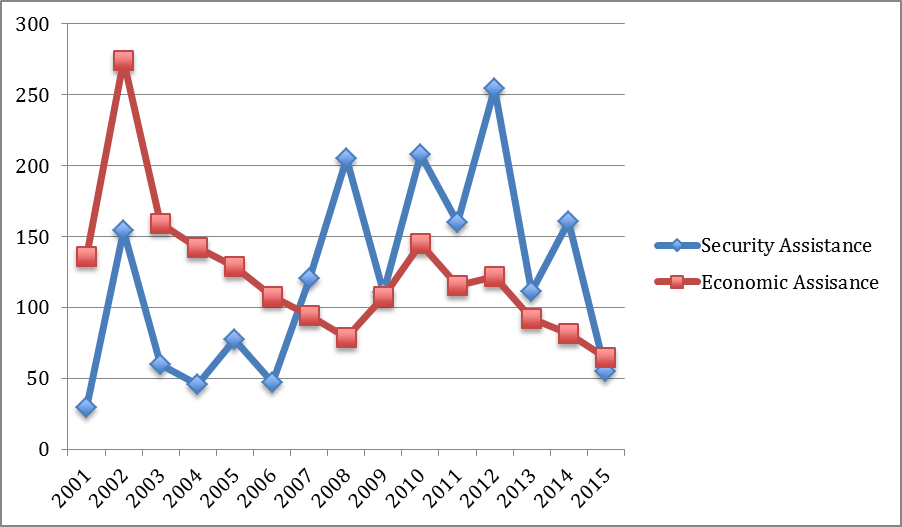

As seen in Figure 1, U.S. security and economic expenditures have varied from year to year. Depending on a range of factors including the nature of the bilateral relationships, since 2007, security assistance topped the amount of economic aid that the region received. Between 2001 and 2006, security aid constituted 43.6 percent of the total economic aid, while between 2007 and 2015 economic aid was reduced to 65 percent of the total security aid. These trends indicate the heightened national interests of the United States in safeguarding internal and regional security threats to Central Asia and ensuring continuing access to regional facilities in support of stabilization efforts in Afghanistan.

Figure 1. U.S. Security and Economic Assistance to Central Asia (in thousands of constant dollars)

Source: Security Assistance Monitor

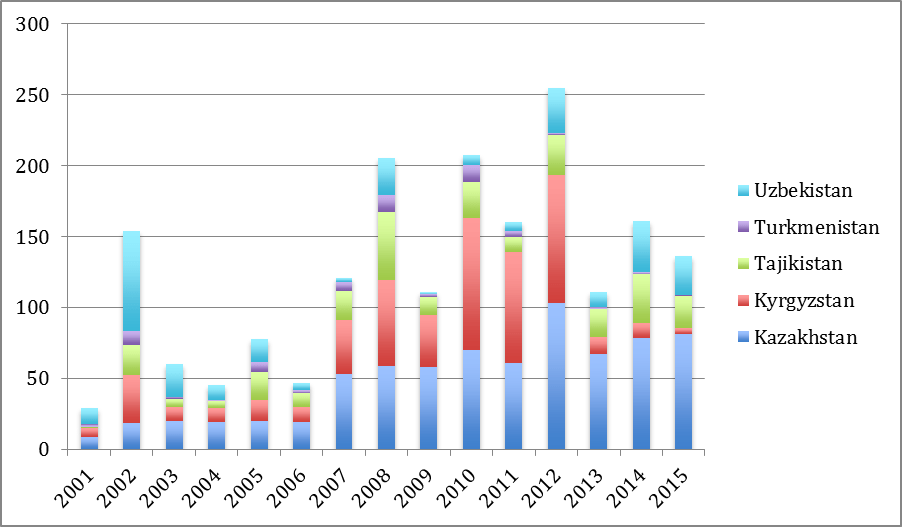

The United States provided over 13,000 Central Asian troops with training through programs such as the Foreign Military Education and Training (IMET), Foreign Military Financing (FMF), the Combating Terrorism Fellowship Program (CTFP), International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement, and Section 1004 Counter-Drug Assistance. Kazakhstan, which sent nearly 300 troops to assist the US-led coalition in Iraq and has contributed to the U.S. State Department’s effort to integrate Afghanistan into the New Silk Road initiative, was the single largest recipient of U.S. security aid, with Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan as distant seconds (see Figure 2). In recent years, the United States stepped up its security assistance programs in Uzbekistan (U.S. military aid restrictions on the country were lifted in 2011) but suspended the training of Kyrgyzstani troops following the closure of its Manas Transit Center in 2014.

Figure 2. U.S. Security Assistance to Central Asian Republics (in thousands of constant dollars) (2001-2015)

Source: Security Assistance Monitor

This aid programs assisted the U.S. military in gaining needed access to facilities in the region, upgrading Central Asian security infrastructure, and improving the preparedness of regional security forces. In Tajikistan, for example, it contributed greatly to developing counterterrorism and counter-narcotics tactical and technical capabilities and enhancing the central government’s coercive capabilities vis-à-vis the regions. In Kyrgyzstan, it aided in building a broader security capacity and facilitating engagement with international organizations. Yet, efforts at modernizing Central Asian armed forces have seen limited success largely due to small defense budgets and the legacies of Soviet military thinking. Only Kazakhstan has made headway in transforming its military into a modern force. It is the only Central Asian republic where the Airmobile Forces Brigade (KABRIG) trained with U.S. assistance programs and received an interoperability status with NATO peacekeeping forces in 2008.

Paradoxically, security assistance aimed at training and equipping Central Asian security personnel to interrupt the large opiates flows from Afghanistan did not reduce the drug trade going through the region. Drug seizures have decreased in Tajikistan, the largest beneficiary of U.S. counter-narcotics assistance (see Table 1). The expressed commitment by other Central Asian governments on drug control did not translate to an equivalent increase in drug seizures relative to the production levels of opium in Afghanistan. Progress toward greater regional security cooperation under U.S. leadership has also been scant. The multi-million dollar Central Asia Counter-Narcotics Initiative (CACI), launched in 2011 to set up, train, and equip counter-narcotics task forces in each Central Asian republic and encourage regional cooperation through the US-supported Central Asia Regional Information Coordination Center (CARICC), has not been a resounding success.

In recent years, Tajikistan received record amounts of U.S. security assistance—$34.7 in 2014 and $22.5 in 2015 million—all while the country was degenerating into single-party authoritarian rule. Kyrgyzstan received the lion’s share of security assistance under Kurmanbek Bakiyev (2005-2010), but his family effectively consolidated control in politics, economy, and the drug trade. The thousands of special operations troops in both countries trained with Washington funding have come from the units under the direct control of the presidents. The improvements in security forces’ capabilities to respond to internal and external security threats appear often to serve the domestic repressive capacities of Central Asian officialdom while enabling leaders to consolidate control over aspects of the lucrative drug trade.

Table 1. Opium Poppy Cultivation in Afghanistan (in thousands of hectares) and Heroin and Opium Seizures (in kg) in Central Asia

|

|

2002

|

2003

|

2004

|

2005

|

2006

|

2007

|

2008

|

2009

|

2010

|

2011

|

2012

|

2013

|

2014

|

2015

|

2016

|

|

Afghanistan

Poppy Cultivation

|

74

|

80

|

131

|

104

|

165

|

193

|

157

|

123

|

123

|

131

|

154

|

209

|

224

|

183

|

201

|

|

Tajikistan

Heroin seizures

Opium seizures

|

3958

1624

|

5600

2371

|

4794

2315

|

2344

1104

|

2097

1386

|

1549

2542

|

1636

1746

|

1132

1040

|

985

744

|

510

490

|

515

627

|

483

774

|

508

990

|

499

1079

|

88.79

611.54

|

|

Kyrgyzstan

Heroin seizures

Opium seizures

|

271

109

|

104

46

|

207

317

|

260

261

|

261

302

|

431

270

|

299

141

|

341

376

|

157

39

|

332

70

|

242

16

|

247

132

|

286

158

|

344.5

46.34

|

166.81

24.91

|

|

Kazakhstan

Heroin seizures

Opium seizures

|

168

13

|

707

192

|

458

353

|

625

669

|

555

636

|

521

335

|

1639

17

|

731

172

|

323

168

|

306

11

|

307

183

|

753

0.1

|

392

49

|

464.38

4.12

|

196.6

2.28

|

Source: UNODC, The Paris Pact Initiative, and the Afghan Opiate Trade Project of the UNODC (The Drugs Monitoring Platform).

The Dangers of Building State Capacity without Concomitant Political Will

The U.S. government has made serious efforts to reduce misuse of equipment and skills through its ongoing evaluations of its security assistance programs, ensuring continued engagement with security actors, and funding and developing programs with a lasting impact on the culture of security institutions in the aid-recipient states. While the U.S. security assistance providers have acknowledged corruption as a barrier to the effectiveness of aid, they have not utilized all available leverage points to effectively ensure that the Central Asian authorities deploy security aid for its intended uses. Once the U.S. government supplies funding, equipment, and training, it loses control over how the facilities, arms, skills, and personnel are then used. For example, in Tajikistan, the United States funded the construction of training facilities for the National Guard and Customs Service (valued at $10 and $20 million, respectively), but there is no further information about either being used even though both are marked as completed projects. In another example, the United States funded the building of the “Friendship Bridge” between Tajikistan and Afghanistan and equipped it with drive-through scanners and modern custom offices at both ends. Although it is used for the largest volume of Afghanistan-Tajikistan cross-border trade, the district where the bridge is located has not reported any drug seizures.

By building state capacity without concurrent accountability, transparency, and anti-corruption efforts, the United States squanders resources.

First, U.S. counter-narcotics assistance to Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan has been largely wasted due to central government collusion in criminal activities and the drug trade. The government of Kyrgyz President Almazbek Atambayev has been implicated in cozy relations with organized crime. In 2014, the Kyrgyz authorities released from prison Kamchy Kolbayev, an influential member of a large Moscow-based crime syndicate who is considered a global drug kingpin by the U.S. Treasury Department. Little explanation was given as to why he was released before the conclusion of his five-year sentence.

Second, by strengthening authoritarian regime coercive capabilities, aid has inadvertently contributed to the rise of discontent. It is possible that such discontent may have prompted the defection to ISIS of Tajikistan’s Lieutenant-Colonel Gulmurod Khalimov, who benefited from five US-funded training courses. Khalimov’s training took placed on the backdrop of the rising religious and political repression in Tajikistan that allegedly provoked the Colonel’s defection. He was vetted by the Pentagon-affiliated Office of Military Cooperation rather than the political section of the U.S. Embassy in Dushanbe, which should have overseen the US-funded military education programs.

Third, the sizable investments in training for counterterrorism operations has played into government narratives stressing the risks of terrorism, but could have been put to more effective use in disaster response and preparedness training.

Conclusions and Recommendations

U.S. interests in Central Asia have always been linked to Washington’s policy priorities toward the greater region. As the United States modifies its military presence in Afghanistan, it will face the need to redefine its goals in the region. Compared to the volumes of assistance to Egypt, Israel, Iraq, and Afghanistan, Central Asian security aid has been a small price to pay for the improved capacity of the Central Asian security institutions and the continued U.S. presence in these states at a time of Russia’s unyielding quest for dominance and China’s growing footprint.

Yet, Washington will need to recalibrate its approach. Instead of the quid pro quo aid-for-access approach used since 2001, Washington should think strategically about the new and persistent security challenges in Central Asia and focus on the limited areas of mutual interest that can be addressed with the available means.

One strategy that has been shown to be effective in producing a desirable and enduring institutional change involves the deeper and longer-term engagement of Central Asian officers in US-hosted educational, training, and social activities, which increase knowledge and appreciation for Western institutions. In Central Asia, the majority of security trainings have been short-term and focused on developing tactical counter-narcotics and anti-terrorism skills through exercises and courses. The number of students participating in the long-term International Military and Education Training (IMET) has been very low compared to those under other programs. The personal ties developed between mid-career U.S. and Central Asian military and security personnel during these exchanges are an important source of knowledge and influence in the region in the long run.

Also, the United States can do better in developing its own indicators of threat assessment and security aid performance in terms of drug trafficking and plausible terrorist threats, instead of relying on claims and evidence provided by governmental recipients. All Central Asian governments have arguably overstated the threat of extremism and terrorism in the region, and the heightened levels of counterterrorism and counter-drug aid feed into, and reinforce, their securitization narrative (as well as the one employed by the Kremlin in pursuit of its agenda).

Central Asian states seek different results from their relationship with Washington, but all need the United States to counterbalance Russian and Chinese influences in the region. This provides the US with important leverage that should be used. The U.S. government needs to more clearly define the oversight, evaluation, and non-compliance consequences of its security assistance packages to each Central Asian state, with close attention particularly paid to programs in Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and Kyrgyzstan. These expectations should be written in a memorandum of understanding that stakes out the levels of U.S. involvement in the host state ahead of time and reduces the U.S. monitoring in phases based on the host states reaching achievement markers. If the host governments are unwilling to provide the desired level of accountability, the United States should prioritize regional engagement with Kazakhstan and those governments that exhibit such will.

Mariya Y. Omelicheva is Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Kansas. Acknowledgment: Office of Naval Research Minerva Initiative Grant “Trafficking/Terrorism Nexus in Eurasia.”

[PDF]