(PONARS Policy Memo) If home is where the heart is, does that mean homeowners are more likely to engage in civic and political activism? Recent events in Moscow suggest the answer is yes. In May and June 2017, tens of thousands of Muscovites took to the streets to protest against plans to demolish Soviet-era housing, even though the quality of the housing is generally recognized to be poor and residents are being offered compensation. Demonstrations against similar demolition plans have been widespread in China in recent years, and have also occurred in Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan. But these may be isolated incidents rather than symptoms of an elevated penchant for civic activism among homeowners. In this context, we examine whether homeownership predicts civic engagement using survey data we collected in Russia, Ukraine, Azerbaijan, and Kyrgyzstan in 2015. We find that homeownership is indeed associated with higher levels of civic engagement, as measured by civic volunteerism, political activism, and voting. However, homeowners tend to be more supportive of the government in these countries. Thus, civically engaged constituencies of homeowners may play to the advantage of post-Soviet governments, though the protests remind us that homeowners can also turn against political authorities if their property rights are jeopardized.

Homeownership and Civic Engagement

Our study seeks to understand the relationship between homeownership and civic engagement. We use the latter term to encompass both non-political volunteering and explicitly political activities (including, but not limited to, voting). Housing scholars, political scientists, and pundits have argued that homeownership tends to increase civic engagement because of the economic stake in owning a home and the way it ties homeowners to local communities, or the sense of security and efficacy it provides. But this claim is controversial, with some arguing that homeownership leads to isolation by reinforcing the “private” dominion at the expense of the public.

The potential effects of homeownership on civic engagement are especially interesting in the post-Soviet context due to the legacy of state-owned housing in the Soviet era, subsequent housing privatization, and the generally low level of civic engagement and lack of generalized trust that these societies are known for. Following the Soviet collapse, the massive dominance of the state housing sector gave way to systems where homeownership is vastly more prevalent.

Housing privatization created a large class of homeowners overnight in a manner that decoupled homeownership from family wealth and income, a connection that makes it difficult to empirically disentangle the effects of homeownership from those of unobservable aspects of family economic status in market-based societies. Although more than two decades have passed since Soviet-era housing stock was privatized, the weak development of housing markets (largely due to credit constraints) means that an unusually large proportion of homeowners in these countries acquire their property via non-market means. Currently, direct privatization accounts for a relatively small proportion of privately owned homes. At the same time, inheritances and gifts are common means for acquiring housing. Subsequent sales, purchases, exchanges, and transferals (via inheritance or gifts) have redistributed private housing assets after the privatization rounds of the early 1990s.

Homeownership Societies

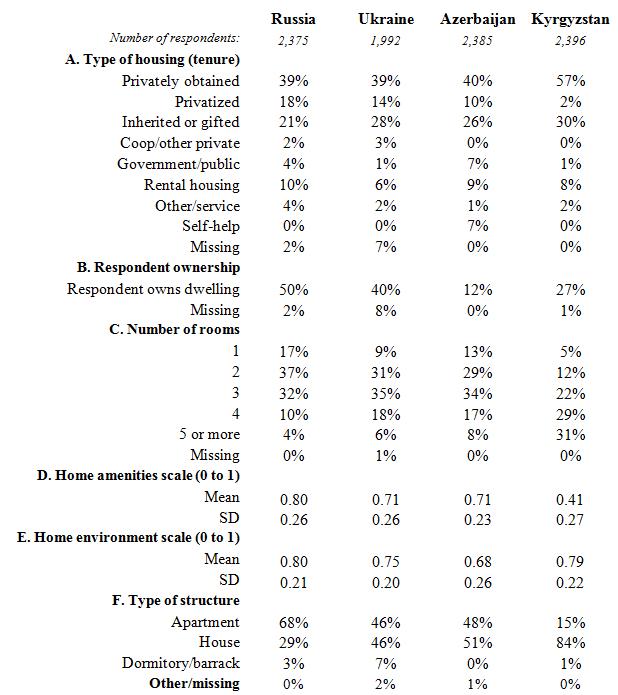

Our data indicate that private ownership of homes predominates in all four countries. In Russia, Ukraine, and Azerbaijan, approximately 40 percent live in homes acquired by purchase or exchange, 21 to 28 percent live in homes acquired via inheritance or gift, and 10 to 18 percent in homes obtained via privatization (see Table 1). Kyrgyzstan stands out for its exceptionally high proportions of directly acquired (57 percent) and inherited (30 percent) homes, and a minimal presence of privatized dwellings (2 percent). Russia and Azerbaijan have the highest proportions of residents in non-privately-owned housing at 18 percent and 17 percent, respectively, with rental housing more common in Russia and government housing more common in Azerbaijan.

Most studies of housing effects rely either on a household-level measure or (less commonly) an individual-level measure. We use both, to distinguish individual-level effects of homeownership from household-level effects. Individual ownership is notably less common among our Azerbaijani and Kyrgyz respondents, which most likely reflects a legal peculiarity in Azerbaijan (where only one person can officially register as the owner of a residence) and the greater prevalence of multi-generation households in Kyrgyzstan (where many adults live in houses owned by their parents or in-laws).

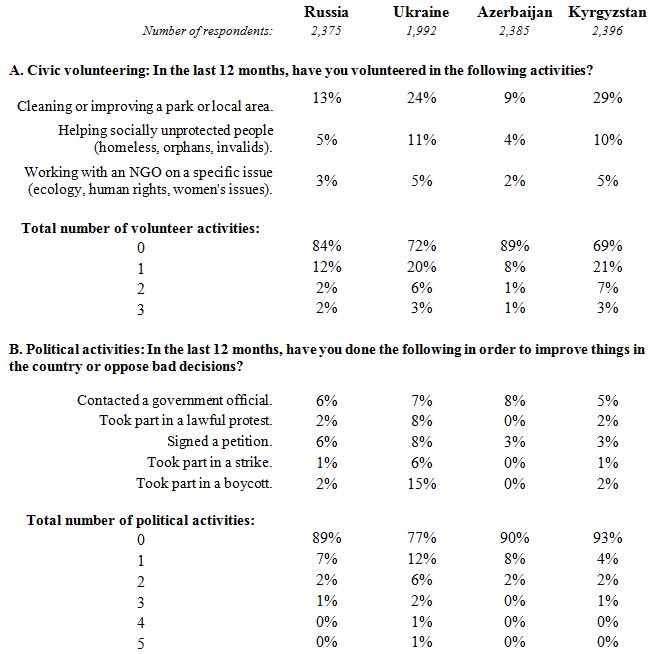

Our measures of civic engagement come from three sets of questions (see Table 2). First, we see if respondents volunteered in three types of civically-oriented activities in the past year:

1. Cleaning or renovating a neighborhood park.

2. Working with a nongovernmental organization that assists people in need (e.g., homeless, orphans, invalids).

3. Working with a non-governmental organization on a specific issue (e.g., environmental protection, human rights, women’s rights).

These forms of volunteering are more common in Ukraine and Kyrgyzstan than in Russia and Azerbaijan, reflecting the greater extent of political freedoms in the former two countries and their more active civil societies. Cleaning a park is consistently the most common form of volunteering, while NGO work is the least. Each individual form of volunteering is rare, so we combine them into composite scales that simply count the number of activities reported by each respondent. Only 11 percent of Azerbaijanis and 16 percent of Russians in our study volunteered at all, compared to 28 percent of Ukrainians and 31 percent of Kyrgyz. About 10 percent of the Ukrainian and Kyrgyz samples volunteered in at least two of the activities.

The second set of questions asked whether respondents participated in five forms of political activities (apart from voting) during the past year:

1. Calling or writing a letter to a government official.

2. Attending a lawful demonstration.

3. Signing a petition.

4. Participating in a strike.

5. Boycotting particular goods.

By these measures, residents of Ukraine stand out as more politically active than citizens of the other three countries, with citizens of Kyrgyzstan and Azerbaijan being the least active. Contacting officials, often cited as a leading form of post-Soviet political activism, is the most typical form of non-voting political activity in Kyrgyzstan, Azerbaijan, and Russia (where it is tied with signing petitions). Participation in protests, strikes, and boycotts is high in Ukraine and exceedingly rare in Azerbaijan, which is not surprising given the extent of authoritarian rule and the repressive response to protests in that country. Summing up the number of non-voting political activities reported by each respondent reveals that only about 10 percent of people in Russia, Azerbaijan, and Kyrgyzstan engaged in any such activities. In Ukraine nearly one quarter did (23 percent) and 10 percent took part in two or more.

The final measure of civic engagement is a simple binary variable indicating whether the respondent voted in the most recent presidential election. These took place in 2012 in Russia and Azerbaijan, 2014 in Ukraine, and 2011 in Kyrgyzstan. We assign a missing value to respondents who were not eligible to vote at the time. Self-reported turnout for the presidential elections was around 72 percent in all four countries, though somewhat lower (67 percent) in Azerbaijan.

Ukraine stands out as having the highest levels of both civic and political activism. Kyrgyzstan exhibits high civic voluntarism but low political activity, while Azerbaijan is low on all counts of civic engagement. In all four countries, civic volunteering is more common than (non-voting) political activity, and only small minorities of 18-49-year-olds participate in any of these activities. Our measures do not cover the full range of behaviors linked to civic engagement, but they offer a reasonable basis for comparing rates of engagement between and within our study countries and assessing the effects of homeownership and other variables.

Activism and Regime Support

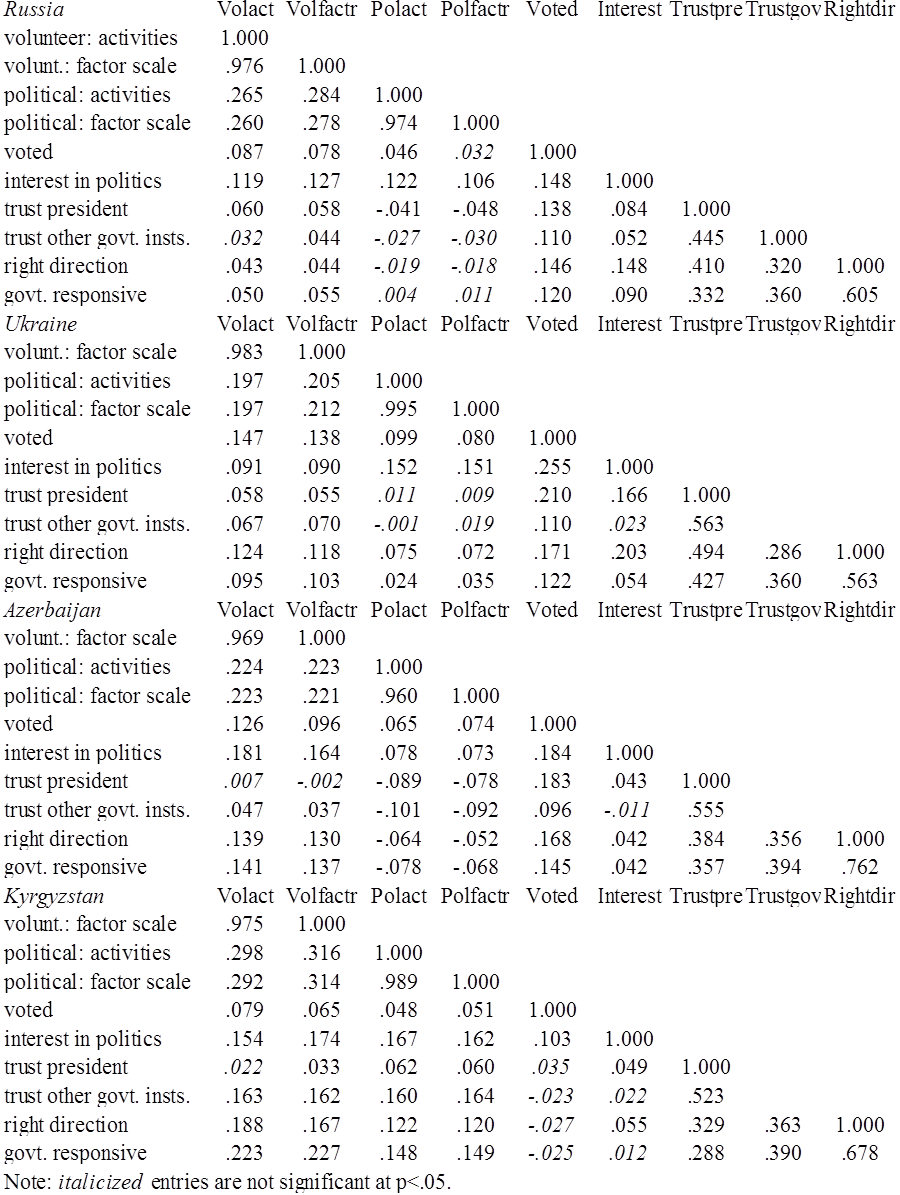

Civic volunteering and political activism exhibit moderate, but statistically significant, correlations in all four countries (see Table 3). This is not surprising: the two dimensions of activism are distinct, yet people who are more active in one tend to be more active in the other. Both forms of activism are correlated more weakly with voting. As an additional validity check, we examine the correlations of our three measures of engagement with a Likert-scaled measure of subjective interest in politics, which are consistently positive, if rather modest in size.

Are civic voluntarism and political activism associated with more critical views of the government? We examine the correlations of our activism measures with four measures capturing different aspects of confidence in the government:

1. Trust in the president.

2. Average trust in the parliament, the courts, and the police.

3. Agreement that the country is heading in the right direction.

4. Belief that the government is responsive to the population’s needs.

Civic volunteering tends to exhibit a weak positive association with support for the government (though in most cases not trust in the president), while political activism is generally uncorrelated with support for the government in Russia, positively (and weakly) correlated with it in Kyrgyzstan and Ukraine, and negatively so in Azerbaijan. Thus, more civically engaged citizens in these countries are not necessarily more critical of the authorities—the opposite may be the case. The positive associations of both civic volunteering and political activism with pro-government views are especially consistent and stronger in magnitude in Kyrgyzstan.

Social Energy

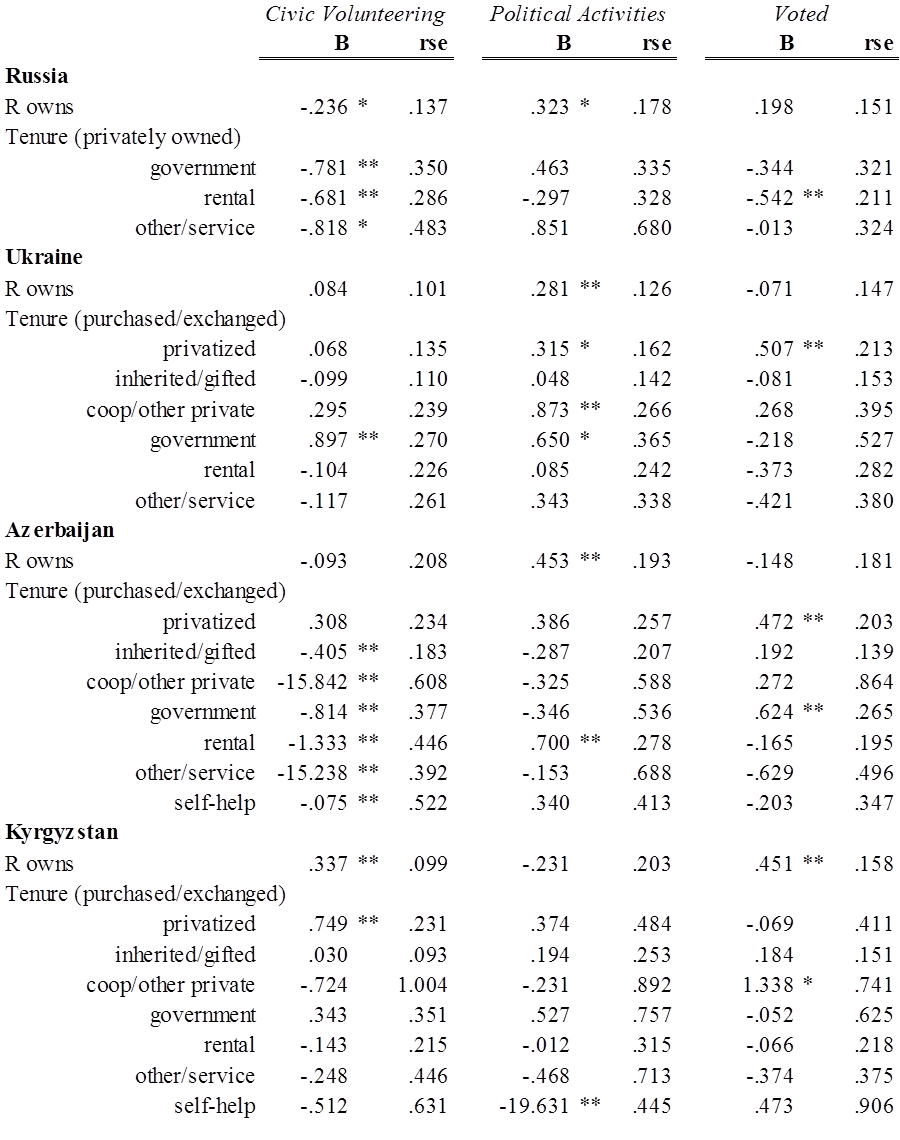

We estimated multivariate regression models for each of our three outcomes of interest (civic volunteering, political activity, and voting) in each country (see Table 4; in this memo we report only the effects of homeownership). By and large, homeowners are more civically engaged than non-homeowners, controlling for a large number of other variables. Not all measures of homeownership have statistically significant positive effects, but every country exhibits at least some effects consistent with the hypothesized relationship. There is only one example of a negative effect: individual homeowners participate less in civic volunteering than non-owners in Russia, but even that effect is net of a consistent positive effect of household-level homeownership. At the household level, the effects of ownership are less consistent and more complex, but generally individuals who live in homes owned by their household are more civically engaged.

Our results underline the necessity of examining individual-level ownership beyond the presented forms of housing tenure in order to understand the relationship between homeownership and political activism. Also, of the three outcomes, voting is the least related to homeownership (this dovetails with similar research on Eastern European countries). Other scholars attribute this weak link between housing tenure and voting in transition countries to privatization, weak housing markets, and the poor average quality of private dwellings. Our findings, with respect to civic volunteering and political activism in four former Soviet societies, suggest that instead of such factors, widespread cynicism about elections is probably the main source behind the null findings regarding voting. Thus, activities other than just voting must be considered in order to understand whether homeownership is related to civic engagement.

Finally, our fine-grained distinctions between forms of both homeownership and non-owned housing revealed some significant differences within each larger category. Only in Russia did we find no differences between privately acquired and privatized housing, and in three countries we found that residence in government housing differs from residence in rental housing. Studies that merge all forms of either private or non-private tenure into coarse categories may miss variations within the two broad groupings. Generally, renters appear to be the least civically engaged group (aside from political activism in Azerbaijan), while in Ukraine and (with respect to voting but not civic volunteering) in Azerbaijan residents in government housing are the most active.

Conclusions

Housing privatization was an important component of the transition from Soviet-style systems to more market-based systems. The creation of large classes of homeowners in Russia, Ukraine, Azerbaijan, and Kyrgyzstan has potential long-term benefits for the development of more civically and politically active citizens. Although observers chronically lament the low levels of civic engagement in these societies, homeownership plays a positive role in encouraging greater levels of involvement—if not necessarily in the form of voting.

Moreover, our measures of engagement tend to positively correlate with measures of regime support: governments of these countries have more to gain than to lose by encouraging homeownership. It may take time for the effects of homeownership on civic engagement to develop and take root. But the sweeping institutional change of housing privatization may contribute to a longer-term progressive development of civil societies in transition countries. Further analysis and research is necessary to elucidate the precise mechanisms underlying the positive links between homeownership and civic engagement in the post-Soviet space.

Of course, the recent housing protests in the Moscow region suggest that regimes should be concerned about adopting policies that challenge the property rights of homeowners: The experience of ownership can foster anti-government activity should homeowners perceive government actions as jeopardizing their claim to their private space. Homeownership and housing issues remain potentially volatile sources of social energy, which could easily turn against prevailing political authorities and institutions. As a Moscow housing protestor quoted by CNN put it: “I want my life to be lived the way I want it to be. I don’t want anyone to think that I am just a figure on a chessboard and they can move me.”

Theodore P. Gerber is Professor of Sociology and Director of the Center for Russia, East Europe, and Central Asia at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Jane Zavisca is Associate Dean for Research and Associate Professor of Sociology in the College of Social and Behavioral Science at the University of Arizona.

[PDF]

Appendix

Table 1. Housing Measures, by Country

Table 2. Civic Activism and Housing Tenure Measures, by Country

Table 3. Pairwise Correlations: Measures of Civic Activism, Interest in Politics, and Regime Support

Table 4. Regression Results, Homeownership Variables

Data and Measures

Data is from the Comparative Housing Experiences and Social Stability (CHESS) survey, which we carried out in the four study countries in 2015. We worked with local teams from each of the four countries to develop survey instruments that cover many aspects of housing, living arrangements, and perceptions of housing, as well as measures of social and political attitudes on major issues. Prior to preparing the questionnaires, we carried out focus groups in all four countries on the topics covered by our survey. Our questionnaires were pretested and revised for clarity (and, in some cases, political sensitivity). They were translated into the appropriate local languages and implemented by our local partners. In each country, we have a nationally representative sample of 2000 and an oversample of 400 respondents designed to help us address specific theoretical questions, constructed as follows: in Russia, residents of four Muslim-majority republics; in Ukraine, mortgagers; in Azerbaijan, internally displaced persons (IDPs); and in Kyrgyzstan, residents in regions with a recent history of ethnic violence. We use weights to correct for the over-representation of these subpopulations and to adjust the samples to conform to known population demographic characteristics. Because we lack independent information on the proportion of mortgagers in Ukraine and they were sampled using a different technique we exclude them from all analyses reported herein. We restricted the age range of respondents to 18-49-year-olds, cohorts most likely to experience housing concerns that may lead to destabilizing political action. Fieldwork was carried out February-May 2015. A note about Table 4: because the first two outcomes (civic volunteering and political activity) are essentially count variables, the appropriate functional form for our models is negative binomial, while the binary voting outcome is analyzed using standard logistic regression. All our models control for the aspects of housing size and quality presented in Table 1, as well as other variables that also relate to civic engagement and may be correlated with homeownership: age, gender, marital status, number of children, education, type of locality, employment status, household income quintile, titular ethnicity, and majority religious affiliation. We also control for IDP status in Azerbaijan and (large) region of residence in Ukraine.