(PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo) Ukraine’s reform process since the Euromaidan is a story of ambivalence. Progress has been limited by leaders who fear losing political control and by entrenched institutional and bureaucratic interests. Many Ukrainians already view the current leaders—who have yet to prove they are genuine reformers—as transitional figures bridging the “old” and “new.” Talking about countering corruption and strengthening good governance in July 2015, U.S. Vice President Joe Biden correctly stated that Ukraine has reached a “moment of truth,” a term that is widely present in Ukraine’s domestic discourse. The survival of the Ukrainian nation depends less on its capacity to counter Russian-backed aggression than on its ability to introduce fair and efficient governance based on the rule of law. Quite remarkably and despite obstacles, progress has been made in a number of areas. New government anti-corruption agencies have been formed, the oil and gas sector has been aligned to EU standards, public procurement is more transparent, and police services are being overhauled.

Government or Society: How is Reform Generated?

In 2014, Ukraine revived its hybrid parliamentary-presidential system. The parliament and the cabinet of ministers both have a strong hand in governance, and the latter became the main policymaking center.[1] However, real power depends on other factors. Currently, President Petro Poroshenko has more power than the constitution formally provides his office, mostly because his party is the largest in the ruling parliamentary coalition. Poroshenko also has influence over the cabinet as half the ministers are from his party. In fact, the “tandem” of Poroshenko and Prime Minister Arseniy Yatseniuk was asymmetric from the start. This imbalance only widened as Yatseniuk steadily lost the public’s confidence—support for his party, the People’s Front, was down to only two to three percent by August 2015.

However, the main thrust for reform comes from bottom-up drivers that have been essential in preventing the consolidation of an “old-new” elite. Civil society has provided the impetus and paths for reform, along with external pressure from the European Union and the International Monetary Fund (IMF).[2] Since the Euromaidan, most reform legislation has been drafted by Ukrainian civil society experts. Quite a few of these “agents of change” were subsequently elected to parliament through various party lists. These active, inter-factional, pro-reform deputies call themselves the “Euro-optimists,” and they represent a new generation of Ukrainian politicians.

Most civil society experts and activists remain outside the government. They work to elaborate and update draft laws, bylaws, reform strategies, and action plans. The largest and most visible pro-reform initiative is a group of community activists, experts, journalists, and academics running an organization called the Reanimation Package of Reforms (RPR). This network offers detailed policy solutions, advocacy, and public communication about reforms. RPR can take credit for some success, in particular recent changes to anti-corruption and public procurement legislation, contributions to the gas sector law, and decentralization policies. Another important initiative is the Strategic Advisory Groups (SAGs), which consists of high-level independent experts. It is funded by the Open Society Foundations and works closely with various ministries. SAGs works on economic policy (deregulation), public administration reform, decentralization, e-governance, law enforcement, healthcare, and education reforms. Other leading organizations include Nova Kraina (New Country) and VoxUkraine, an independent international expert network.

Today, there are improved liaison channels between government and civil society. The RPR, for example, has specific units responsible for policy advocacy. And the Cabinet of Ministers established the Reform Support Center to improve dialogue with civil society entities. Civil society has been at the forefront of monitoring reform progress. All the abovementioned organizations share the results of their monitoring. VoxUkraine, which incorporates advice and feedback from Ukrainian experts based at EU and U.S. universities, provides reform tracking data on their website.

Progress Areas

Despite power plays, administrative resistance, and public skepticism, reform progress has been achieved in Ukraine in various areas. These are outlined below.

Anti-corruption policy

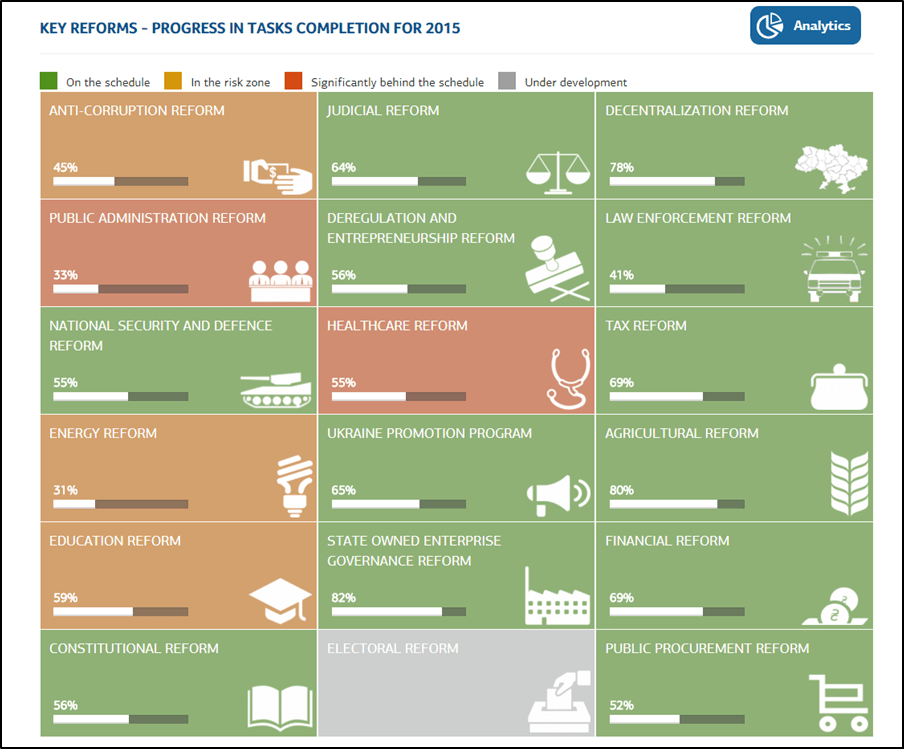

The National Reform Council (NRC) was created in the second half of 2014. It serves as a policy dialogue platform and informal decisionmaking institution on a wide spectrum of reforms. The NRC is not a constitutional entity, so its decisions are not formally binding, but it is the institution at the center of Ukraine’s reform process. The NRC is a mechanism for the president, prime minister, speaker, ministers, chairs of parliamentary committees, and select civil society leaders to meet regularly to prioritize policies, assess the status of reforms (see Figure 1), and discuss progress reports by relevant officials. Its staff members are funded by the Open Society Foundations and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development—its officers have higher salaries than public officials. As of August 2015, the NRC has had nine regular meetings and a number of informal activities. All the Council’s stakeholders have agreed to accept its recommendations and reform paths.

Figure 1. The NRC website homepage outlining the main areas for reform (12/1/15)

In addition to the NRC, two anti-corruption bodies are under construction: the National Anti-Corruption Bureau of Ukraine (NABU) and the National Agency for the Prevention of Corruption. Artem Sytnyk, the director of NABU, the more important agency, was appointed after a transparent selection process run by an independent commission. There are still ongoing policy debates about NABU’s institutional status and how it will work with the Prosecutor General’s office. Poroshenko would like NABU to be linked to the Prosecutor General whereas civil society advocates seek it to be institutionally independent.

Legislation adopted in February 2015 introduced some safeguards for the independence of NABU’s work:

- NABU staff are to have fairly high salaries: from 22,000 hryvnia (about $950) for detectives and 60,000 hryvnia ($2,600) for directors.

- Officers are not allowed to apply for NABU positions if they worked in the last five years in any anti-corruption unit at any law enforcement agency.

- External audits are to be conducted annually to assess NABU’s effectiveness and operational and institutional independence. Auditors are to have excellent professional reputations, not be public officials, and have working experience in investigative agencies or courts abroad.

- NABU investigators would have the power to monitor bank accounts based on court orders.

There are, however, some gaps. For example, the president or a simple parliamentary majority can dismiss the agency’s director based on a negative annual report by an external auditing team appointed by the president, parliament, and cabinet of ministers. Thus, both the president and prime minister could conceivably protect themselves and others from NABU investigations.

Energy market reforms

Ukraine’s Law on the Gas Sector was adopted in June and is in accordance with the EU’s latest energy market legislation (the “Third Energy Package”). The law was negotiated by the Ukrainian government, the IMF, and EU experts. It clearly stipulates the legal, economic, and managerial foundations of gas market functioning based on free competition, consumer protection, and delivery security. When fully implemented, the law will guarantee revolutionary change in the Ukrainian gas market, which was one of the most corrupt and non-transparent sectors of the Ukrainian economy for decades. Currently, international companies are working with Ukraine’s Naftohaz, a monopolist that handles the extraction, transportation, and delivery of oil and gas, to help it comply with the new regulations. Also in June, the Parliament approved a law stipulating Ukraine’s compliance to the standards of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI).

Police reform

Over 2,000 new police officers started patrolling Kyiv in July. Each went through a selection process and three-month training program. Though they are not experienced, there is an obvious positive change in the public perception of the police because of this reform. There has been no indication of corruption, bribery, or brutality by any of the new officers. Five more cities (Lutsk, Kharkiv, Uzhhorod, Mykolayiv, and Odessa) have new police programs and Dnipropetrovsk will soon follow. Ukraine’s Law on the National Police stipulates the transformation of all Soviet-style “police militia” into modern police forces based on best practices from the West (and Georgia). The expectation is that the nationwide transformation will take two to three years.

Property ownership transparency

In July, parliament opened access to the property register, which includes real estate, land, and vehicles. This new legal act provides public access to information on property registered under anyone’s name. This should serve as a tool to counter corruption by revealing unexplained inconsistencies between public servants’ declared income and their real living standards.

Decentralization and constitutional reform

In February 2015, the law on the Voluntary Amalgamation of Territorial Communities went into effect. The law seeks to promote viable and self-sufficient communities that operate with their own managerial and financial resources. Importantly, they are to provide access to administrative and social services for their local communities. The process of amalgamation is rather slow, however; according to the plan, the reform should be completed by the end of 2017.

Related and more contentious are constitutional amendments on decentralization and local governance. This issue is heavily politicized due to the need to accommodate the Minsk-2 agreements (which are interpreted differently by the different sides). Russia insists that constitutional changes must be negotiated with separatist leaders in the Donbas and include a “special status” for the regions. Kyiv refuses to negotiate on the constitution with the Russian-installed separatists since it sees them as illegitimate.

Public procurement reform

In the summer of 2015, the parliament approved amendments to Ukraine’s public procurement legislation to bring it in line with international standards. The aim was to have Ukraine be in compliance with the WTO Agreement on Government Procurement, thereby allowing Ukrainian companies to bid on projects in the 43-member-state public procurement market, estimated at $1.7 trillion. On the domestic front, over 300 companies joined a pilot electronic procurement system called Prozorro, which promotes fair competition among businesses seeking to provide supplies to the government.

Judiciary reform

Ukraine’s High Council for Justice, which is responsible for appointing and monitoring top judges, was reformed by new legislation adopted in February 2015. Draft constitutional amendments that involve substantial judiciary reforms were introduced in parliament in November, after review by the Council of Europe’s Venice Commission, an international advisory body. However, extensive judiciary reform faces insufficient political will and strong resistance from within the judicial system. Entrenched judges are trying to conserve the old system and Ukraine’s top leaders remain hesitant to create a truly independent judiciary (as judges who are fully out of their control may one day act against them if motivated to do so by political opponents).

Reform of the public administration and the civil service

The Law on Civil Service was approved in its first reading in April and finally adopted in early December. It stipulates essential reforms in accordance with European civil service standards. It divides political and administrative positions in the government and provides new procedures for recruiting officials.

Limiting oligarchs’ power

The once-untouchable oligarchs are under pressure. Ihor Kolomoisky was fired as governor of the Dnipropetrovsk region (after he helped stabilize the political situation there in 2014). The government has been trying, with gradual success, to limit his control of Ukrnafta, Ukraine’s major (state-owned) oil and gas company; a positive step was removing his handpicked managers this past July. Investigations have been launched against Dmytro Firtash and his enterprises. The richest Ukrainian oligarch, Rinat Akhmetov, is likely to lose control over key parts of the energy sector. At the same time, Poroshenko, an oligarch himself, has not quite divested his numerous business assets as he had promised, which gives his critics grounds to accuse him of “selectively countering oligarchy.”

Conclusion

The post-Euromaidan reform process is driven less by top-down political will than by strong bottom-up pressures from civil society activists and organizations, coupled with external institutional pressures (mainly the EU and the IMF). Such a model for implementing reforms requires a deep and sustained public dialogue and more time for consensus-building. This makes the overall process of reform slower than if it were imposed from the top down, but it also makes it more grounded and comprehensive. At the same time, the country’s longstanding administrative traditions are a continual source of resistance. Ukraine’s reforms remain a work in progress.

Oleksandr Sushko is Research Director of the Institute for Euro-Atlantic Cooperation, Kyiv, Ukraine.

[PDF]

[1] There are some exceptions; for example, security issues fall under the National Security and Defense Council, which is chaired by the president.

[2] Substantial policy changes in Ukraine are often determined by IMF conditionality. Certain changes connected to macroeconomic stability and austerity measures are beyond the scope of this memo, as are some specific policy areas such as education, healthcare, and e-governance.