(PONARS Policy Memo) The oil- and gas-rich states of the Caspian Sea basin—Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan—registered phenomenal growth throughout most of the 2000s. However, the heady days of resource-fueled development now appear to be over, and local governments are suddenly struggling to overcome massive budget deficits, devalued currencies, and overall economic stagnation. What led to the current economic crisis gripping the Caspian basin states? In what ways are state planners in Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan addressing the challenges? Although many of the reforms recently announced by these governments appear dramatic and novel, they ultimately represent little deviation from the countries’ longtime development strategies, which prioritize economic modernization without political transformation.

What is Happening and Why Now?

1) A triumvirate of external shocks

In addition to the dramatic drop in world energy prices over the past several years, the economic crisis gripping the Caspian littoral states is rooted in two further external shock factors: the collapse of the Russian ruble after U.S.-led sanctions were imposed in 2014, and the significant slowdown in China’s economic growth and energy demands since 2015. In the decade prior to this recent triumvirate of shocks, Eurasia had become increasingly economically integrated. In addition to the well-known labor movement and remittance networks uniting Russia and its southern neighbors, the Caspian basin states also sought to diversify their export and import markets by increasing trade with China and ramping up oil and gas sales in the east. With their main trading partners also reeling from the global slowdown, these three factors have together wreaked havoc on the largely undiversified hydrocarbon-based economies of Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan.

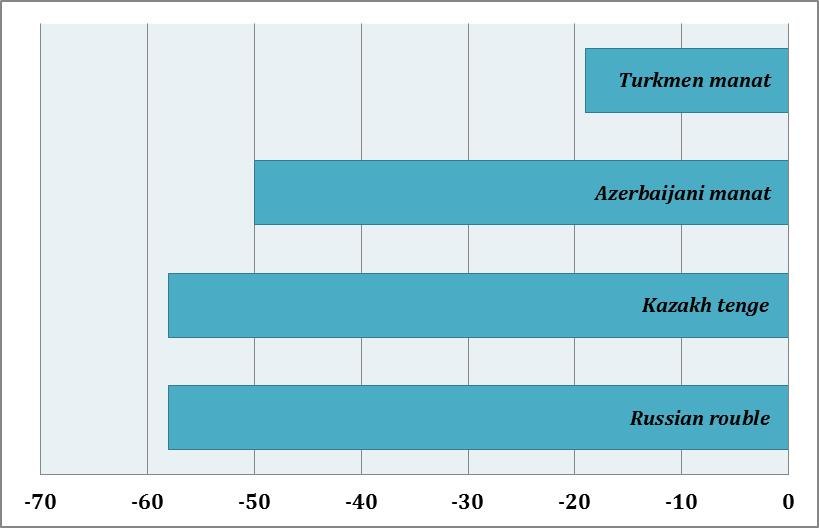

In 2015, the countries all saw their GDP growth rates plunge from 8-10 percent averages in the first decade of the 2000s to around 1.2 percent in Kazakhstan, 1.1 percent in Azerbaijan, and a dubious 6.5 percent in Turkmenistan. Kazakhstan abandoned its U.S. dollar peg for the tenge in August 2015, while Azerbaijan devalued its manat twice in 2015. Turkmenistan has similarly seen huge devaluations in its manat, though observers suggest that it remains grossly overvalued (see Figure 1). The currency debacle led Kazakhstan’s planners to dip into its sovereign wealth fund, Samruk-Kazyna, to the tune of $28 billion to prop up the tenge. In a rare moment of insider criticism being made public, Berik Otemurat, who was chief executive of the country’s National Investment Corporation, decried the fund’s 17 percent value drop since its peak in August 2014, falling to just over $60 billion in December 2015:

“We are eating up the National Fund. The money we have been lucky to accumulate is the only money we have to capitalize on. I think the government needs to focus on the National Fund’s investment management.”

Otemurat was later sacked for his decision to speak out, but the trend he indicated was not unique to Kazakhstan. Many sovereign wealth funds (which are often supported by resource revenues) across the globe are under intense pressure: Saudi Arabia’s fund has just lost 14 percent of its value, while Norway is tapping its own fund for the first time ever in 2016.

Figure 1. Currency devaluation (avg. percent change, Jan. 2014 – Jan. 2016)

2) Resource wealth: not cursed but mismanaged

Over the past decade, leaders in the Caspian region have, to varying degrees, paid lip service to economic diversification to reduce their overdependence on oil and gas exports. However, most of these policies have actually followed typical rentier state spending patterns, whereby petrowealth is invested in extremely large and costly infrastructure projects that allow elites to funnel money offshore and distribute patronage to their supporters. Examples include various projects that the governments claim will diversity their economies by promoting tourism. In Azerbaijan, the government spent an estimated $8 billion to host the first European Games in 2015, while Kazakhstan’s official (and likely modest) estimates to host the EXPO-2017 next summer are around $3 billion. Meanwhile, in Turkmenistan, the government has poured billions of dollars into developing Arwaza, an essentially empty seaside resort city on the Caspian.

Regardless of the exact price tag of these white elephant projects, the overarching point is that they disproportionately benefit elites at the expense of the general population. They are luxury expenditures rather than social investments. But rather than assuming that these patterns of wealth mismanagement are simply the result of some “resource curse,” it is important to emphasize that the governments did have alternatives when energy prices were high. They could have chosen more sensible, long-term investments to meet the needs of the citizenry. Instead of addressing these less flashy infrastructural needs, officials largely worked to entrench their own interests through promoting hydrocarbon-based economies—and now they are paying the price. To deal with the fallout, leaders in Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan have recently introduced a range of new initiatives to diversify their economies, but it appears that it all may amount to too little, too late.

Facing the Fallout: Three Tacks to Restructuring

Kazakhstan

Of the three Caspian basin states, Kazakhstan has gone the furthest to develop an economic restructuring plan. In late 2015, the government announced a massive privatization push, which includes the complete or partial sale of hundreds of 783 state-owned companies between 2016-2020. Among those on the list are three of Kazakhstan’s major energy firms—KazMunaiGaz (oil and gas), Kazatomprom (uranium), and Samruk-Energy (coal, renewables, and other electricity-generating assets)—as well as numerous other major firms like Kazzinc, Temir Zholy, Kazpost, Air Astana, Kazakhtelecom, and even the Caspian Sea port of Aktau. In an editorial in The Astana Times, “Plan of the Nation—the Path to the Kazakhstan Dream,” President Nursultan Nazarbayev justified the blueprint as necessary to advance the country’s modernization agenda in this time of global economic turmoil, while a later opinion piece in the same outlet argued that the privatization agenda would achieve three goals: raising revenue to help cushion the impact of the economic slowdown, streamlining Samruk-Kazyna to increase the sovereign wealth fund’s efficiency, and “injecting” outside capital and expertise to spur private-sector competition.

Kazakhstan’s restructuring plans have already been met with suspicion by foreign observers and investors, who are unlikely to look favorably on assuming the state companies’ massive debts. KazMunaiGas, for example, has recently required multi-billion dollar injections of cash to stay afloat, and its future prospects look dim. Investors also remain wary of Kazakhstan’s reputation for corruption and having a weak regulatory environment. To combat this, the government recently announced a new “Astana International Finance Center” to serve as a regional financial hub following English law and offering the financial industry’s catchiest new services, like “green” finance and Islamic banking. Looking more like desperate measures for desperate times, rather than a calculated modernization agenda, Kazakhstan’s proposed reforms are nothing short of sweeping. Yet as in the other countries, these new economic liberalization plans stop far short of any substantial political liberalization.

Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan began to experience serious economic difficulties in early 2015. After the shocking devaluations of February and December 2015, when the Azerbaijani manat depreciated by almost 100 percent, the government turned its attention to efforts that might mitigate the crisis and alleviate the situation by promoting more business activity. Dozens of licenses for entrepreneurial activities were eliminated, while tax and custom authorities were rendered more transparent. Apparently trying to break the monopolistic nature of the economy, the government also eliminated some duties and taxes for import-export operations. And in September 2016, the State Committee on Property Issues launched a new “Privatization Portal” to provide potential investors with information about state privatization efforts and legal frameworks. At the macro level, the government established the position of Presidential Assistant on Economic Reform tasked with creating a roadmap for economic reforms. The team began by prioritizing the sectors of Azerbaijan’s economy that they deemed best positioned to create jobs and attract investments. The government also established a new Financial Market Supervisory Chamber, giving it some functions previously managed by the Central Bank. Moreover, several other committees were established with different functions and tasks. Finally, the government heeded the tourism sector’s long-standing priorities to facilitate international travel, and further liberalize its visa regime.

However, in-depth analysis shows that these actions have not yet resulted in any significant impact. The economy remains monopolistic and foreign investors are not rushing in. Most of the reforms do not target the root problems and are more “cosmetic” in nature. The lack of free competition, no respect for private property rights, as well as the absence of independent courts, have, and will, continue to make these new economic initiatives fruitless. As a result, the Azerbaijani government is likely to face serious problems in near future. To fulfill its commitments to expand oil and gas development in the region, including the SOCAR-backed TANAP (Trans-Anatolian) and TAP (Trans-Adriatic) pipeline projects, Azerbaijan is in dire need of massive investment. Meanwhile, the Oil Fund of Azerbaijan is currently the only mechanism that can stabilize the financial situation in the country, but it will not have enough funds to invest into other governmental commitments. At a certain point—probably in the near future—the government will need to seek external loans from World Bank, IMF, or other agencies, which may require significant reforms in all sectors of Azerbaijan’s economy.

Turkmenistan

While Kazakhstan appears to be in restructuring overdrive and Azerbaijan is wavering somewhere in the middle, Turkmenistan clearly represents the other end of the response spectrum. It has one of the least diversified economies in the region. Its hydrocarbon sector accounts for about 35 percent of its GDP, 90 percent of exports, and 80 percent of fiscal revenues. In mid-July 2016, President Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov issued a decree abolishing the Oil and Gas Ministry, as well as the State Agency on Management and Use of Hydrocarbon Resources—transferring their duties to the Cabinet of Ministers. Observers are uncertain about the reasons or potential effects of the move, but it is clear that state-owned firms Turkmengaz and Turkmennebit are suffering immensely in the current economic environment. Meanwhile, the government remains staunchly opposed to additional involvement from foreign energy companies in the country, and seems instead to be turning inward for solutions—like a recent demand that business elites contribute $100,000 to state coffers. Restructuring in Turkmenistan has looked more like a mere reconfiguration of its other extractive economy: popular extortion.

Looking Ahead: Too little, too late?

Overseeing rapid growth in the period of high energy prices, the governments of Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan have staked their domestic legitimacy on the promise of economic development at the expense of democratization. It is not yet clear what impact the region’s economic crisis will have for the ruling regimes’ stability, but it is unlikely that it will lead to any sudden upheavals or calls for democracy. For several decades now, the leaders in the Caspian basin have warned their populations about the threat of chaos and turmoil that accompany democracy. Stirring collective memories of the 1990s-era hardship, and pointing at the civil strife in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, politicians and state-controlled media have succeeded in instilling a deep-seated fear of political liberalization and “premature” democratization. Flush with resource rents to bolster their claims, the governments in Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan largely attributed their economic success in the 2000s to their centralized system of rule.

Yet with this fallacy now exposed through a triumvirate of external economic shocks, another confluence of international events also seems to be working as a counterbalance to potential calls for more democracy in the region. Namely, a spike in terrorism and civil strife, combined with the rise of autocratic and xenophobic political movements, have recently marred some of the world’s leading democracies, including the United States, Britain, Austria, and perhaps most forebodingly of all, Turkey and the Philippines—where during this past summer, much blood was shed and thousands of political prisoners now fill jails. While the Caspian basin states may indeed be doing too little too late to escape their economic woes unscathed, with this turbulent global political situation as a backdrop, ordinary citizens are not likely to be clamoring for political restructuring in the short term. Advocates of economic and political reform might therefore hope for Kazakhstan to succeed in its sweeping restructuring effort, which has the potential to effect lasting change. Although it is off to a rocky start, the structure of the broader reform agenda at least has the potential to show one way forward for the Caspian region beyond resource dependency—and maybe, one day, beyond autocracy.

Natalie Koch is Assistant Professor in the Department of Geography, Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs, Syracuse University.

Anar Valiyev is Associate Provost at ADA University, Baku, Azerbaijan.

[PDF]