How did the dramatic events of 2014, including the annexation of Crimea and the onset of violent armed conflict in eastern Ukraine, transform the opinion of Russians regarding their ethnic identity, nation, and state? Some have seen these events as sparking a dramatic upsurge in xenophobia and Russian nationalism, marking a new chapter in Russian identity politics. Others have questioned how much change has actually taken place. Evidence from two nationally representative surveys, one taken in May 2013 and the other in November 2014, indicates that what Russia experienced is much better characterized as a “rally ’round the leader” effect than as an upsurge in nationalism per se. In part, this is because Russian nationalism was already strong before the crisis in Ukraine emerged, so current events tapped into preexisting sentiment more than transformed it (with the exception of an evident increase in negative attitudes toward Ukrainians). What did change substantially, however, was the level of support for Vladimir Putin, which surged to nearly half again its May 2013 level. At the same time, concerns about economic and social problems deepened. Together, these findings indicate the main effect of the 2014 events on public opinion was to create a “rallying effect” around Putin personally but not to transform mass consciousness in a way that is likely to benefit the Kremlin in the long or even medium run.

The NEORUSS 2013 and 2014 Surveys

The surveys we analyze here were carried out by Russia’s established and respected ROMIR polling agency as part of the University of Oslo’s “New Russian Nationalism (NEORUSS)” project, funded by the Research Council of Norway (2013) and the Fritt Ord Foundation (2014) and commissioned by principal investigators Pål Kolstø and Helge Blakkisrud. The May 8-27, 2013 survey included a nationally representative sample of 1,000 respondents interviewed face-to-face long before the Ukraine crisis. The November 5-18, 2014 survey replicated most of the questions from 2013 and also asked new questions to assess the effects of the crisis in Ukraine and subsequent armed conflict. This new survey was carried out according to the same methodology and included 1,200 respondents. On some issues, we were also able to get a sense of longer-term trends by referring to data from a 2005 Russia-wide survey of 680 respondents on ethnic relations by the Moscow-based Levada Center that was organized by Mikhail Alexseev.

No True Surge in Nationalism

The NEORUSS surveys find little evidence of a surge in nationalist sentiments among Russians between May 2013 and November 2014. Levels of ethnic and civic pride, desires to defend dominant ethnic group privileges, and perceptions of national distinctiveness all changed only marginally. In fact, most of these sentiments have remained about the same for nearly a decade.

- Ethnic pride stayed constant. Most respondents—55 percent in 2005, 53 percent in 2013, and 56 percent in 2014—said they were “very proud” of their ethnic identity and about 35-40 percent in each survey said they were “mostly proud.”[1] These small differences are well within the margin of sampling errors.

- Civic pride increased, but only a little. The number of respondents who were “very proud” to be citizens of Russia rose from 44 percent in 2013 to 52 percent in 2014, but this came mainly at the expense of the category of people who were already “somewhat proud.” The difference between the number of respondents who reported being proud of their Russian citizenship remained about the same relative to those who reported being not proud. Given the scale of events that took place in 2014, these findings hardly point to a massive nationalist rallying effect.

- The dominant ethnic group’s sense of entitlement to privileges remained stable. About three-quarters of respondents in 2013 and 2014 believed that top government jobs should go first and foremost to ethnic Russians (russkie)—with about 39 and 40 percent, respectively, supporting this idea fully. Roughly half of the respondents in both years fully agreed that ethnic Russians must play the leading role in the Russian state, with another one third or so backing this notion partially. Stability in a sense of entitlement over time is also reflected in support for the slogan “Russia for [ethnic] Russians” (Rossiia dlia russkikh): 63-66 percent expressed complete or partial support for the slogan in 2005, 2013, and 2014.

- The sense of Russia’s national distinctiveness changed little. In both 2013 and 2014, a plurality of respondents (about 35 percent) considered Russia to be a unique civilization, neither Western nor Eastern.

- Even attitudes on how Russia should relate to the West were not radically transformed, although the survey does register a moderate hostile shift. If in 2013, 60 percent of those venturing an answer thought Russia should treat the West as a “partner” and 13 percent as a “friend,” in 2014 the figures went down only to 51 percent and 8 percent, respectively—together still a clear majority of the Russian population (even when non-responses are included). Even in 2014, the share of Russians thinking the West should be treated as an “enemy” was just 13 percent (up from 5 percent in 2013), while 27 percent thought it should be considered a “rival” (up from 22 percent).

Other important nationalist views changed in more pronounced ways, but pointed in different directions. On the one hand, xenophobic exclusionist sentiments somewhat hardened while acceptance of ethnic Ukrainians as “fraternal people” significantly declined (this is an old imperial and Soviet notion reinvigorated in the Kremlin’s framing of Russia’s putative motivations for Crimea’s annexation). On the other hand, general acceptance of ethnic diversity in Russia increased and support for further territorial expansion of Russia weakened.

- Public support for deporting all migrants from Russia—legal and illegal and their children—rose from 44 percent in 2005 to 51 percent in 2014, which is unlikely due to sampling error alone. That said, these figures reflect both full and partial support for the demand, and the number of those who fully supported this radical exclusionist measure remained practically unchanged at about 23 percent since 2005. Most of the change in at least partial support appears to have taken place prior to the 2014 events, increasing only by about 4 percent—within the surveys’ margin of error—from 2013 to 2014.

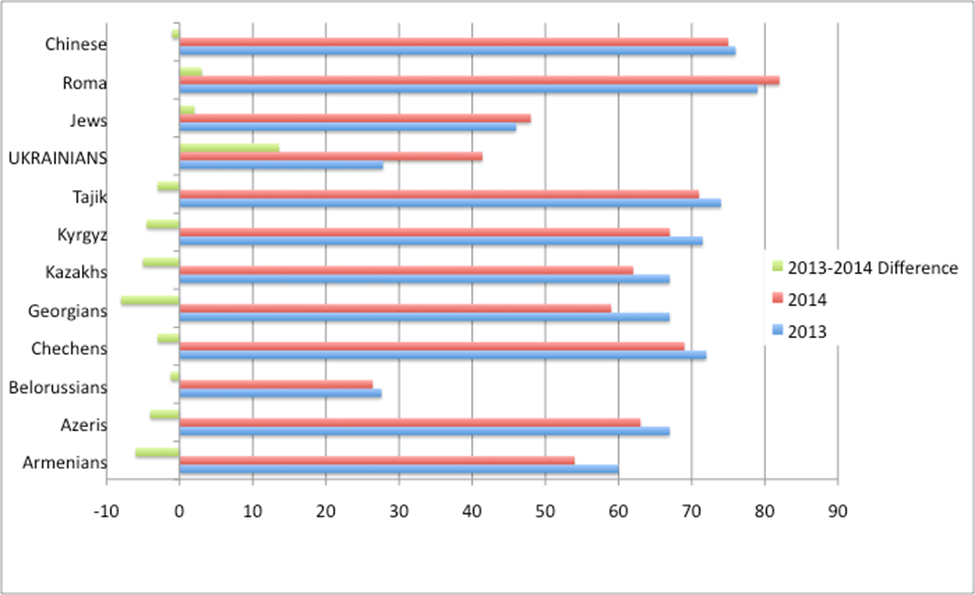

- The number of respondents strongly opposing their family members marrying ethnic Ukrainian migrants spiked from 28 to 42 percent between 2013 and 2014—an outlier in the general trend for somewhat greater acceptance of migrant non-Russian ethnics as marriage partners. In this sense, Russian respondents appeared to be “defraternizing” with Ukrainians (Figure 1) but not other groups. The fact that opposition to marrying ethnic non-Russian migrants on average changed little from 2005 to 2013 further suggests this “defraternizing” was an artifact of changing Russia-Ukraine relations since 2013.[2]

- In 2014, more respondents stated that ethnic diversity strengthened rather than weakened Russia, which was not the case in 2013. The 2005 data suggests that most of this shift took place from mid-2013 to late 2014. The number of respondents who felt the term russkie (Russians by ethnicity or culture) referred exclusively to ethnic Russians dropped from 42 percent in 2013 to 30 percent in 2014.

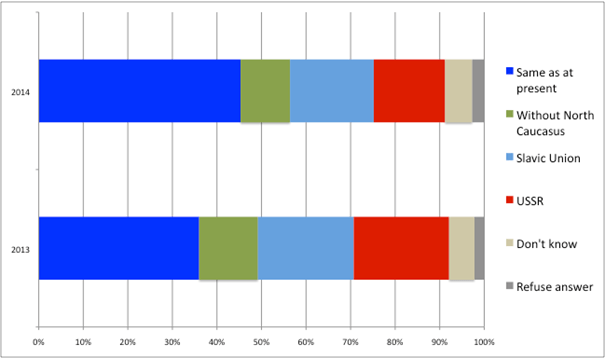

- At the same time, Russians remained more wary of including other ethnic group members into their state through territorial expansion. From 2013 to 2014, the number of respondents who preferred expanding Russia’s territory—either to bring Ukraine and Belarus into a Slavic union or to incorporate all territories of the former Soviet Union—dropped from 47 to 38 percent. In 2013, the majority of Russians (56 percent) supported some form of territorial enlargement, while in 2014 a plurality (of about 45 percent) supported the status quo (Figure 2).

Rallying Round the Leader: A True Surge

The biggest beneficiary of true public opinion change in Russia from 2013 to 2014 was the country’s leader, Vladimir Putin. Readiness to vote for Putin, positive valuations of Putin’s system of rule, and Putin’s nationalist credentials all increased strikingly. The NEORUSS surveys show that “rally ’round Putin” effects have been robust—lasting more than eight months after Crimea’s annexation and several months after Russians started experiencing economic problems associated with declining oil prices and Western economic sanctions.

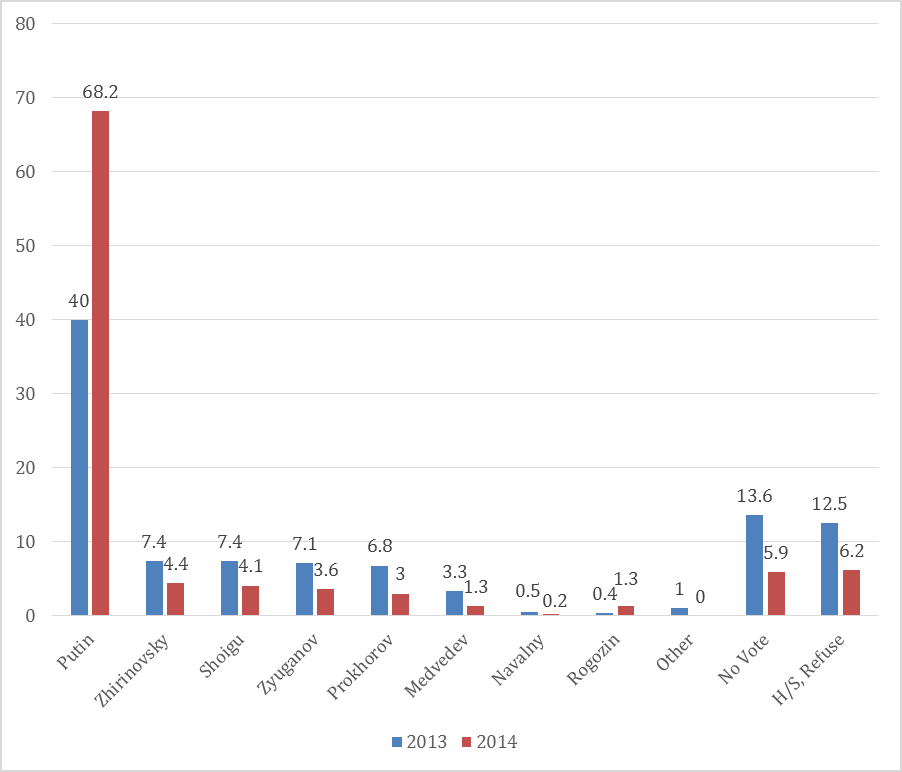

- The share of all respondents declaring they would vote for Putin if the presidential election were held on the day of the survey leapt from 40 percent in 2013 to an impressive 68 percent in 2014 (Figure 3). Support for Putin not only surged at the expense of almost all other potential candidates—including the notoriously hypernationalist Vladimir Zhirinovsky—but also reduced the number of respondents who said they would not vote at all.

- Views of Russia’s political system turned from predominantly negative to predominantly positive. When respondents were asked to rate “the political system that exists in our country today” on a scale from 1 (“very bad”) to 10 (“very good”), the average score shot up from 3.3 in 2013 to 6.0 in 2014.

- Confidence in Putin as a leader who could deal with national identity issues also surged. Only 14 percent of respondents in 2013 named Putin as the most competent defender or promoter of Russia’s national identity from among a set of likely presidential candidates—just barely ahead of such other leaders as Zhirinovsky, who was picked by 9 percent. In 2014, 34 percent of respondents now selected Putin and only 4 percent indicated Zhirinovsky. Meanwhile, the number of those who said it was hard to answer that question dropped from 27 to 18 percent. Similarly, the number of respondents who felt Putin was the most competent among Russia’s prominent politicians to deal with migration from Central Asia, the Caucasus, and China jumped from 15 to 32 percent.

Economic Rain Clouds Looming Over the Parade

As the euphoria over Crimea slides further into the past—particularly given Putin’s reliance on Russia’s hitherto robust economic growth as an important source of legitimacy—the NEORUSS survey data provide grounds to suspect the rallying effects may erode. Most notably, Russians’ assessments of their country’s economy and their families’ well-being significantly worsened between May 2013 and November 2014, and many Russians at least partially link this decline to Crimea’s annexation.

- In May 2013, a majority (54 percent) believed the country’s economy had remained stable over the course of the previous year, 19 percent thought it had improved, and 21 percent felt it had deteriorated. Eighteen months later, a stunning 55 percent reported the economy had gotten worse in the previous year, with just 9 percent seeing improvement and 30 percent no change.

- Respondents’ reporting of their own families’ economic position over the past year reflects the same pattern. In 2013, 19 percent saw improvement, 60 percent sensed no change, and 18 percent perceived decline. By 2014, a full 45 percent were bemoaning a worsening in their personal economic situation, with only 8 percent citing improvement and 42 percent sensing no change over the previous year.

- The NEORUSS survey also sought to assess whether Russians felt Crimea’s acquisition was having negative effects. Since one might wonder whether respondents would give frank answers to an interviewer, the survey not only asked people directly but also used an indirect method (an “item count” technique that allows researchers to estimate the share of people holding a view without any individual having actually to state it openly). Boiling down both these findings, the survey indicates that between 38 and 55 percent of respondents believed Crimea’s acquisition would “cost Russia too dearly,” hardly boding well for the Kremlin. At the very least, these findings highlight conflicting sentiments resulting from the clash of surging pride in the country’s leadership on the one hand and ambiguous economic assessments on the other.

Implications

The NEORUSS surveys indicate it would be a mistake to describe what happened in Russian public opinion in 2014 as a surge in Russian nationalism, ethnic or otherwise. Instead, it should be considered primarily a “rally ’round the leader” effect. This has significant implications for both observers and policymakers. For one thing, it means Putin’s bold moves in 2014 did not create a new wave of nationalism that might be expected to recede back to “normal” levels later. Instead, Putin tapped into a preexisting Russian nationalism that was already quite strong, mobilizing it for support where previously it was not helping him much. He also clearly reaped “leadership points,” support deriving more from the perception that he is a dynamic and decisive leader than from any specific action—something that has long underpinned his popularity but had seemed to be fading in recent years. Questions those interested in Russian politics should be asking moving forward, then, include: (1) Will Putin continue to be seen favorably by Russian nationalists or will this issue start working against him; and (2) Will other factors eventually override or undermine the rallying effect we observe?

On question (1), the NEORUSS surveys suggest it will be difficult for Putin to sustain nationalist support because nationalists themselves are divided. While many still back expanding Russia to the borders of the former USSR (people we may call “imperialists”), others (whom we might call “xenophobes”) not only oppose this but want to deport migrants from post-Soviet states who are already in Russia. The 2014 events appear to have somewhat moderated xenophobia and also reduced territorial expansionism, but the shares of both xenophobes and imperialists remain significant and if they return to pre-2014 levels, Putin will face challenges trying to reconcile them. The growing hostility toward Ukrainians as a people detected in the survey may also complicate Russia’s relations with an important neighbor state in the future. Given an additional finding that the Russian public has generally bought into the Kremlin-led media characterization of Ukraine as a weak and illegitimate state, however, Putin may be able to overcome those problems with new massive public relations campaigns.

On question (2), the economic worries detected in the survey indicate people may one day tell their leadership something like: “OK, we are happy with Crimea’s return, but that is now in the past and we still want economic improvement.” The Kremlin might respond by attempting to offer Russians more territory instead of economic development, hoping this will again divert their political attention from material worries. But with support for expanding Russia’s territory declining since 2013, it is far from certain such a policy could work as the Kremlin might hope. Of course, Russia’s leadership also possesses many other ways to shape public opinion, including a vice-like grip on the political coverage of Russia’s highly influential television channels. But bad economic realities (and battlefield deaths if they reach a large scale) will be harder to hide or spin than will events in other countries, even neighboring ones. And the NEORUSS surveys overall suggest that the Kremlin has been successful mainly in generating a rather narrow rallying effect, not in transforming public opinion in a fundamental way that works in favor of the current leadership in the long run. Thus, while public opinion was more of an enabler than a constraint when it came to Crimea, it is unclear that this can be replicated with new territorial moves.

Figure 1. Share of respondents who strongly opposed their family members marrying migrants belonging to ethnic groups other than their own

NOTE: Responses of “don’t know” and “refuse to answer” are excluded from the denominator of the calculations here. The number of “don’t knows” and refusals differed within only a couple percentage points by ethnic group in both years. The number of those who said ethnicity did not matter for marriage was constant and therefore also left out of the denominator; respondents who picked that option were not asked their views for each specific group. In total, these data missing from the denominator made up about 28 percent of the sample in 2013 and about 20 percent in 2014.

Figure 2. Preferences for the territorial boundaries of the Russian Federation

Figure 3. “If presidential elections were held today, for whom would you vote?”

(percentage of entire adult population)

[1] To compare these results over time, the “missing data” (i.e., “don’t know” and “refuse to answer”) are excluded here and thereafter, unless otherwise stated. For ethnic pride, the missing data constituted 3.5 percent of respondents in 2005, 2 percent in 2013, and 2.4 percent in 2014.

[2] The 2005 Levada survey data was available regarding Chechens, Chinese, Armenians, and Azeris.