As war continues to victimize Ukraine, various observers and participants have proposed a number of potential solutions to the conflict, ranging from greater regional autonomy to federalism to partial territorial breakup. While politicians are engaging in the most prominent debates and decision-making, the perceptions of Ukraine’s population will be central to the success of any such political solution. What exactly are the public’s perceptions and how subject have they been to change?

We address this question with data from a new survey that interviewed the same set of Ukrainian citizens three times during 2014. The chief finding is that despite the major costs of war, Ukrainians (even in the east) tend to agree strongly that Ukraine should remain undivided, with many (especially in the west) believing this is something worth fighting for. However, major divides exist on exactly what form this unity should take. Judging by public sentiment, issue-specific autonomy arrangements and some form of limited decentralization offer a much greater chance of eventually unifying the country than would sweeping reforms that invoke the term “federalism.”

Decentralizing Reforms on the Agenda

The Russian government, along with the leaders of the self-proclaimed Donetsk People’s Republic (DNR) and Luhansk People’s Republic (LNR), declare that the latter regions should be part of Ukraine but only if they gain a special constitutional status that allows them to carry out their own foreign and economic policy. Reforms like this, involving far-reaching autonomy and regional vetoes over much central policymaking, are widely called “federalism” in Ukraine and Russia. Russia and its allies also demand the legitimization of the DNR and LNR leadership through local elections to be held in October 2015.

Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko was elected in May 2014 on a platform of constitutional reforms that includes deep administrative and fiscal decentralization. This, however, would not go so far as Russia and the insurgents demand. In particular, it stops short of introducing any special constitutional autonomous status for any of the regions. Having been declared conforming to Ukrainian basic law by the Constitutional Court, these more limited constitutional reforms have already won the endorsement of both the Council of Europe’s Venice Commission (a legal advisory body) and Ukraine’s Constitutional Committee and are now up for parliamentary approval. Observers currently expect the reform to pass later this summer or during the fall.

What do Ukrainian citizens think about different possible forms of decentralization?

The UCEPS Survey

The findings reported here come from the Ukraine Crisis Election Panel Survey (UCEPS), designed by the authors and Harvard University professor Timothy Colton. The survey was funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation, the Ukraine Studies Fund, and the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute, and implemented by the reputable Kyiv International Institute of Sociology. The first survey wave took place May 16-24, 2014, with interviews of a sample of 2,015 citizens of Ukraine designed to be nationally representative (except for Crimea, which had already been annexed by Russia). Of these, 1,406 were re-interviewed during June 24-July 13, 2014, and 1,373 were interviewed in a third survey wave during November 29-December 28, 2014. The survey included the Donbas[1] fully in the first wave, though as rebel control advanced and the zone of combat widened, some respondents dropped out of the survey, especially in the Luhansk region. The margin of error is no greater than 3.3 percent.

Support for Regional Decisionmaking Autonomy

In the most general terms, the UCEPS found that there is broad popular support for policy autonomy in the regions. In May 2014, 43 percent agreed that policy and administrative power should be equally divided between the central government and the regions while another 25 percent favored giving the most decisionmaking power to the regions. This far outweighed the share backing greater centralization. The statements that “all decisions should be taken by the central government” and “most decisions should be taken by the central government” met with the agreement of only 5 and 8 percent, respectively. These figures were nearly the same in the November-December 2014 wave of the survey. In this round, however, support for a balance between central and regional power increased to just over the 50 percent mark, while again 25 percent backed more regional power and only 11 percent backed a country dominated by the central government.

One important example of the sort of decentralization Ukrainians appear to support involves language policy. In the May 2014 survey wave, 68 percent of respondents agreed that “each region of Ukraine should have the opportunity to make Russian the official language in its locality,” while only 25 percent were opposed. Even in the western territory of Galicia[2], known as a center of ethnolinguistic Ukrainian nationalism, a clear majority (54 percent) supported this. Relatedly, 67 percent of Ukrainians nationwide censured the attempt by some members of the March 2014 emergency parliamentary session that followed the overthrow of President Viktor Yanukovych to repeal the 2012 Law “On the Principles of the State Language Policy” that afforded such language autonomy (this attempt was vetoed by acting president Oleksandr Turchynov, though the fate of the law remains in question).

That said, the ongoing conflict has appeared to take its toll on the tolerance of western Ukrainians for other regions’ language preferences. While the overall national majority in favor of language autonomy remained robust at 64 percent in June-July 2014, the share of Galicia’s population supporting this dropped from a majority in May to just 32 percent during June-July (and 31 percent in November-December). Support for linguistic autonomy also declined in other regions, although it still remained a majority (54 percent) nationwide by the end of 2014.

Support for “Federalism” in Ukraine

The Russian leadership (including President Vladimir Putin) has demanded a more comprehensive system of regional autonomy for Ukraine, calling for Kyiv to adopt a “federal” system of government. In the May 2014 survey wave, only 18 percent of respondents tended to agree with the statement: “Some experts have proposed federalism as a way to preserve the unity and territorial integrity of Ukraine. What do you think about this? Do you agree or disagree that Ukraine should adopt a federative form of state structure?” Here, however, we find a major regional divide: In Ukraine’s western regions (not just Galicia), pro-federalism sentiment was at just 4 percent while in the Donbas it was at 62 percent.

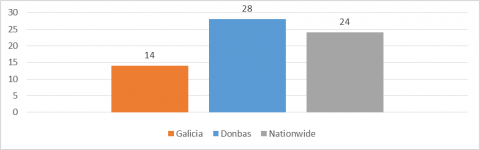

After the war had raged for several months, Ukraine’s leadership agreed to a ceasefire that, among other things, would grant the kind of special autonomous status to the breakaway regions that Russia’s federalism proposal envisioned. While the ceasefire itself was broadly popular, with about four-fifths of the population supporting it from Galicia to the Donbas, the autonomy component met with widespread disapproval—even in the Donbas, where only 28 percent of the population expressed support (see Figure 1). While the population of Ukraine generally supports greater regional autonomy and decentralization, the UCEPS findings indicate that with the partial exception of the Donbas, Ukrainians do not support more far-reaching reforms.

Figure 1. Approval of special Donbas autonomy as called for in the 2014 cease-fire agreement (percent, November-December 2014)

Support for State Dismemberment

Some policy observers, primarily based abroad, have argued that Ukraine should just forget about Crimea and perhaps even the Donbas and move on. Advocates of partition suggest that this might not only make European integration more realistic but also excise some of the largest electorates that have challenged the most European-oriented parties and leaders.

The UCEPS finds that such ideas meet with little sympathy in Ukraine. For one thing, we find that the support for regional autonomy discussed above does not include backing a right to secession. When presented with the statement “Do you agree that every region of Ukraine should have the right to secede if a majority of its population votes for it?” answers were generally in line with the findings on “federalism.” An overwhelming majority (69 percent) backed it in the Donbas, but few (22 percent) supported it nationwide, with two-thirds of the country being opposed.

This brings up a related question. Would the Donbas vote to secede from Ukraine if given the opportunity? The UCEPS did not ask this question directly, but it did ask people in the June-July 2014 wave whether they agreed that “Ukraine would be better off without some of its parts.” Even in the Donbas, only 24 percent affirmed this statement. Of this 24 percent in the Donbas, asked specifically whether they would part ways with a series of specific territories, 37 percent identified Galicia, 40 percent Transcarpathia, 40 percent Crimea, and 52 percent the Donbas itself! A large majority of Donbas residents, therefore, are not willing to say that Ukraine would be better off without the Donbas. This at least suggests that Donbas residents do not actually want to exercise the secession option, though of course it may also mean that they just think the rest of Ukraine would be worse off if they were to secede. Thus while the UCEPS provides clear evidence that most Donbas residents favor an autonomy arrangement that would give them the right to secede, it at least suggests that that they would not actually want to exercise that option.

Looking at figures for the country as a whole, a meager 8 percent averred in June-July 2014 that Ukraine would be better off without any of its territories, including Crimea. This indicates that the argument that Ukraine could more successfully reform and join Europe without Crimea and the Donbas was falling on deaf ears. One might wonder whether war fatigue changed these figures, but if anything Ukrainians appeared to become more resolute in championing territorial integrity over 2014. In the November-December survey wave, only 7 percent nationwide agreed that Ukraine would be better off without some of its parts, essentially the same as in the early stages of the war.

Perhaps most importantly, feelings for territorial integrity were strongly felt. As many as 42 percent across Ukraine in the May 2014 survey wave went so far as to agree that “the preservation of Ukraine’s territorial integrity is a goal that justifies the risk of civil war.” This was significantly greater than the 35 percent who disagreed (the rest found it hard to say or refused to answer).

Conclusion

Overall, judging from public opinion research from May to December 2014, Ukrainians appear quite unlikely to acquiesce to any solution to the current crisis that includes recognition of territorial losses. Calls for federalism are also deeply unpopular nationwide and are unlikely to be accepted outside the Donbas. So long as citizens have the right to freely vote in presidential and parliamentary elections, any move toward either of these solutions involves high levels of political risk for policymakers. Although a federal solution might help bring the disaffected Donbas back into Ukraine’s active political fold, and while we cannot rule out that the rest of Ukraine’s citizens would one day acquiesce to this, the result might also be to exacerbate societal divisions by antagonizing other parts of Ukraine. It seems unlikely that a Ukrainian leader with aspirations of staying in office for the longer run will seriously undertake such measures without securing very large concessions on other issues that are politically popular enough to offset the domestic political losses.

At the same time, there still exists broad national support for some decentralization and more limited forms of autonomy in realms such as language policy. Current constitutional reform efforts to redraw the administrative map and devolve certain executive functions are more in line with public opinion than calls for federalism or dismemberment. Indeed, in November-December 2014, 50 percent of the population advocated a roughly equal balance between central and regional authority rather than favoring either regional or central power, and a plurality of Ukrainian citizens believed that Poroshenko’s party stood for precisely this. The fit of Poroshenko’s reforms with public opinion is far from perfect, however, and they look unlikely to satisfy the Donbas, which remains much more sympathetic to a farther-reaching federalism than the rest of the country.

The UCEPS findings also suggest that so long as Russian and pro-Russian forces continue to occupy parts of Ukraine, there will be Ukrainians in the mood to fight for Ukraine’s territorial integrity. With Russia showing few signs of reversing course, the political situation in Ukraine and Russia appears likely to be hot for the foreseeable future.

Henry E. Hale is Professor of Political Science and International Affairs and co-Director of PONARS Eurasia at the George Washington University.

Nadiya Kravets is GIS Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute and a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies at Harvard University.

Olga Onuch is Assistant Professor of Politics at the University of Manchester and Associate Fellow in Politics at Nuffield College at the University of Oxford.

[PDF]

[1] This includes Donetsk and Luhansk regions. In this text, reference to the Donbas includes both government-controlled and occupied localities.

[2] This includes Lviv, Ternopil, and Ivano-Frankivsk regions.